In the previous article, we have learned how to set up the Hückel determinant for conjugated linear molecules based on the topology of the -bonds. In this third article, we will apply the method to cyclic molecules and will derive some other useful properties.

Physical Chemistry: The Simple Hückel Method (Part II)

In the previous article, we have learned how to set up the Hückel determinant for an aromatic molecule based on the topology of the pi-bonds. In this second part, we are going to learn how to calculate from the determinantal equation both the eigenvalues and the eigenvectors, corresponding to the orbital energy and orbital functions of the molecular system.

Continue readingRetro programming nostalgia IV: Acid/Base Balance and Titration (Part II)

This second article continues my journey of acid/base titrations. In the previous article (https://daniloroccatano.blog/2020/04/14/acidsand-bases-equilibrium/), I showed how to calculate an acid-base equilibrium for strong acids and bases. This article also describes subroutines for titrations of monoprotic weak acids and bases. The method I used solves the pH calculation precisely and is based on an article published in the chemistry journal “Rassegna chimica” by Prof Luigi Campanella (and Dr G. Visco) in 1985. I received a copy of the article from the author while attending his analytical chemistry course at the University “La Sapienza” in Rome. I remember writing a program for the study of titrations was fun and stimulating, but it helped me understand the subject thoroughly. I recommend that the young reader try to convert the program into a modern language more familiar to you (e.g., Python) to understand its functioning better.

Continue readingA Practical Introduction to the C Language for Computational Chemistry. Part 3

Sphere. From Space, from Space, Sir: whence else?

Square. Pardon me, my Lord, but is not your Lordship already in Space, your Lordship and his humble servant, even at this moment?

Sphere. Pooh! what do you know of Space? Define Space.

Square. Space, my Lord, is height and breadth indefinitely prolonged.

Sphere. Exactly: you see you do not even know what Space is. You think it is of Two Dimensions only; but I have come to announce to you a Third — height, breadth, and length.

Square. Your Lordship is pleased to be merry. We also speak of length and height, or breadth and thickness, thus denoting Two Dimensions by four names.

Sphere. But I mean not only three names, but Three Dimensions.

Adapted from:

Flatland: A romance of many dimensions by Edwin A. Abbott

ADVENTURE IN SPACELAND

In part 2 of this tutorial, we have learned how to use arrays and how to read atomic coordinates from a file. In the appendix, you can find an example of the solution to the exercises given in the previous tutorial.

In this third part, we are going to learn how to generate three-dimensional coordination of atoms in a cubic crystal lattice and how to calculate non-bonded molecular potential and the force acting among them.

Continue readingA Practical Introduction to the C Language for Computational Chemistry. Part 2

In the first part of this introduction to C language, we have learnt the basic of the C language by writing simple programs for the calculation of the non-bonded interaction between two particles at variable distances. Some solutions to the first part exercises are reported in the appendix of this article.

In this second tutorial, we will learn how to use arrays data types and how to load them with a set of data read from a file. We will also use these data to perform numerical calculations and write results in output files.

Arrays and Pointers Datatypes

The program that calculate the energy of interaction between two particle doe not take in account the actual position in space of the two particle but only their distance. If we want to study the dynamics of a system composed by multiple atoms in a tridimensional space, it is way more convenient to represent the and calculate their interactions by using the coordinates directly to evaluate the distances.

Continue readingThe Dandelion (Taraxacum Officinalis) and OpenCV

The dandelion’s pallid tube

Astonishes the grass,

And winter instantly becomes

An Infinite Alas —The tube uplifts a signal Bud

And then a shouting Flower, —

The Proclamation of the Suns

That septulture is o’er.– Emily Dickinson

The yellow flowers and the delicate and beautiful inflorescence of Dandelion catch the attention of both romantic and curious souls. The aerial consistency of the fine silk decorated seeds that glance to the sunlight as crystalline material became the favorite subject of the inspired photographers and the toy of amused children. Besides the grace of its forms, other interesting and the curious secret is hidden in its phloem fluids. In fact, if you cut one of the stems of the plant, a milky, sticky liquid will flow out of the wound resection. This latex is going to polymerize at 30-35 oC in a few minutes in a yellow-brown quite solid mass. Around the year 1982, I have annotated this observation but I could not find in my later notes further follow-ups study on the topics. It was a casual observation but I didn’t know at that time that this latex is indeed very useful. A variety of the Taraxacum (Taraxacum koksaghyz, Russian Dandelion) was used in Russian and American to produce a replacement of the natural rubber from Brazil during WWII that was in shortage because of the war. Many studies are in progress to exploit the lattice of Taraxacum and Taraxacum brevicorniculatumas, a convenient replacement for the rubber plant lattice. A recent study has shown the presence of rubber particles in the lattice of these plants in 32% proportion composed prevalently by poly(cis-1,4-isoprene) at >95% purity (www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2091/11/11). The brownish lattice condensate that, as I reported in my note, forms after exposing the latex to the air for several minutes is caused by the presence of the polyphenol oxidase (PPO) enzyme that produces the fast coagulation of the latex by catalysing the oxidation of polyphenols. Genetic engineering the plant makes it possible to reduce the amount of PPO in the latex, making economically competitive use of this resource for latex production.

Continue readingCrystal Structures

Cristallo e fiamma, due forme di bellezza perfetta da cui lo sguardo non sa staccarsi

Italo Calvino, Lezioni americane. Sei proposte per il prossimo millennio.

The successful reception of my previous posts on calculating the lattice energy, the calculation of the Born-Haber cycle and the Madelung constant motivated me to write more about the crystal structures of inorganic and organic compounds. In this series of articles, I will briefly introduce the crystallography. It does not pretend to be comprehensive, but it is meant to give just a flavor of this fascinating topic.

What is a Crystal?

At the atomic level, a crystal is solid with regular arrangements of atoms in space. Depending on the material, these arrangements have different symmetry properties that generate beautiful symmetric shapes at the macroscopic level.A regular and infinite arrangement of atoms can be visualized as a vast and complex network of interconnected particles. Each atom, with its unique properties, contributes to the overall complexity and variety of the system. The repeating patterns of the atoms create an endless and fascinating display. This assembly of atoms forms the basis of the world of matter, showcasing the intricate and beautiful nature of the smallest units of our universe.

We start introducing the Bravais lattice’s fundamental concept to describe and classify these atomic arrangements..The term “Bravais lattice” is a name given to a mathematical concept used to describe how points are arranged in a crystal. It is named after Auguste Bravais, a physicist from France who studied crystals in the 19th century. Bravais introduced the idea of different types of arrangements and symmetry in crystal structures. His work was important in understanding how crystals are classified based on their symmetry. The Bravais lattice is a fundamental concept in crystallography that describes the periodic arrangement of points in a crystal lattice. It provides a framework for classifying and categorizing different types of crystal structures based on their symmetry and arrangement of lattice points.

Chimica Fisica: La Termodinamica, La Meravigliosa Cattedrale Della Scienza. Parte I.

Indipendentemente dai motivi del culto, le antiche cattedrali invitano ad un’ammirata contemplazione, ispirano rispetto e quiete. Anche il visitatore più disinvolto non si esimere dal moderare la voce, non insiste in argomenti futili: delle navate, l’eco delle sue stesse parole sembra destare insolite suggestioni. L’impegno di generazioni di architetti e di artigiani e’ stato dimenticato, le loro impalcature sono state rimosse ormai da lungo tempo, i loro stessi errori sono stati cancellati dai secoli. Il monumento che essi crearono, ora compiuto e perfetto, ci appare come la testimonianza di un disegno sopraordinario. Se evochiamo in noi il ricordo di un cantiere in attività, con il rumore ritmato dei martelli, le voci ed i gesti degli operai, l’odore stantio del legno e di tabacco, alle splendide structure che ora ammiriamo non possiamo attribuire altro significato che quello di essere il frutto di un ordine imposto alla mera fatica umana.

Anche la scienza ha i suoi templi, costruiti con gli sforzi di pochi architetti e di molto operai, e di fronte ad essi proviamo lo stesso sentimento. Anche in questi templi l’atmosfera e’ solenne, e forse lo e’ a tal punto da condizionare l’espressione stessa del pensiero scientifico, che una lunga tradizione vuole assai severo e formale.

G.N. Lewis, M. Randall -“Thermodinamica”, Leonardo Edizioni Scientifiche, Roma (1971).

INTRODUZIONE

Gilbert Newton Lewis e Merle Randall nella introduzione alla prima edizione del loro autorevole testo di termodinamica chimica descrivono la termodinamica come la cattedrale della scienza. La loro non è solo una concessione poetica di un’epoca ancora permeata dal romanticismo scientifico, ma una meravigliosa analogia per questa fondamentale disciplina della scienza che più di ogni altra contiene le leggi arcane che goverano il nostro Universo e il suo destino.

In questa serie di articoli riporto alcuni appunti su argomenti vari di termodinamica chimica che possono essere utili come riferimento o come materiale didattico.

Continue readingProgramming in Awk Language. LiStaLiA: Little Statistics Library in Awk. Part I.

In the following previous Awk programming articles

Awk Programming II: Life in a Shell

Awk Programming III: the One-Dimensional Cellular Automaton

I have briefly introduced this handy Unix program by showing two examples of elaborate applications. In this fourth article of the series, I will offer a little library of functions that can be used for the essential statistical analysis of data sets. I have written (and rewritten) many of these functions, but I have spent little time collecting them in a library that can be used by other users. So this article gives me the motivation to achieve this target. Unfortunately, I didn’t extensively test the library, so I am releasing it as an alpha version. If you spot errors or improve it, please just send me your modified code!

READING DATA SETS

We start with a function that can be used to read data from a text file (ascii format). A good data reader should be able to read common data format such as comma separated (cvs) or space separated data files. It should also be able to spik blank lines or lines starting with special characters. It would be also handy to select the columns that need to be read and also check and skip lines with inconsistent data sets (missing data or NaNs). This is what exacty work the function ReadData() given in the Appendix. But shall we see it more in details.

ReadData(filename,fsep,skipchr,warn,range,ndata,data)

The function read the data from a file with name provided in the variable filename. The program skips all empty record, those starting with one of the characters contained in the regular expression skipchar. For example, a regular expressions such as skipchr=”@|#|;” skips the occurrence of the characters “at” or “hash” or semicolomn. The variable warn is used to check the behavior of the program if alphabetic characters or NaN or INF values are present in the data. If the variable is set to 0, the function gives a warning without stop the program, if set to 1 then the function terminate the program after the first warning.

The field separator is specified in fsep and it is used to set the awk internal variable FS and define the separator between data. The variable can be assigned with single character such as fsep=” “ or fsep=”,” or ESC codes such as fsep=FS=”\t” for tab-delimited.

The column in the data record can be read in two ways by set the element zero of the array range[]. For range[0]=0, a adjoint range of data is specified by setting the first element is at range[1] the last one in range[2]. For range[0]=1, the first element in range[1] is the number of data to read followed by the specific field in the record where the data is located.

Continue readingThe Father Secchi’s Sundial of Alatri

- Tempus breve est.

- Tempus volat, hora fugit.

- Festina lente.

- Semper amicis hora.

- Vivere memento.

Some of My Favourite Sundial’s Mottos

Alatri is a picturesque town in the province of Frosinone, 80 km southeast of Rome. Located in the heart of Ciociaria, it overlooks the Sacco Valley from the highest point on top of a hill. Among other important attractions, the historical center of the city treasures one of the best-preserved megalithic constructions in Ciociaria. Megalithic architecture is characterized by imposing stonework (also called megalithic or Cyclopean ruins). The one in Alatri is an impressive perimeter wall. The wall, known as the polygonal walls, is built around the highest point of the town, the acropolis. It was constructed for fortification and ritual worship purposes. The megalithic civilization reached the highest level of stone masonry during the Neolithic period. Major centers existed in different Italian regions and throughout Europe from Greece to England. Alatri is just one of the megalithic towns of Ciociaria. Other nearby impressive remains can be found in Ferentino and Veroli.

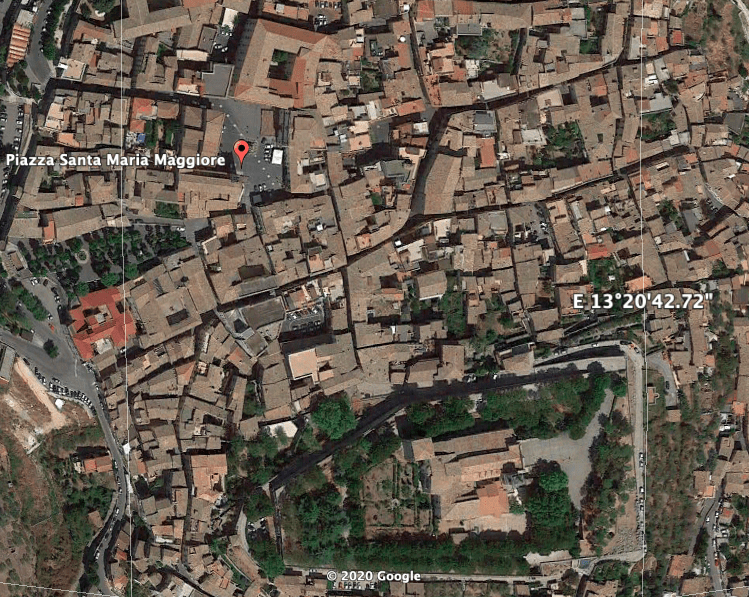

I will write more about megalithic architecture in another article. In this context, I will describe a more recent but still beautiful architectural embellishment. This embellishment has a practical function. It is prominently visible in the Piazza Santa Maria Maggiore, the town’s central square. I am referring to the beautiful sundial (OROLOGIO SOLARE in italiano, see photo below). It was built in 1867 on the facade of the Palazzo Conti Gentili. The architect Giuseppe Olivieri constructed it based on accurate calculations by Padre Angelo Secchi. He was a renowned Jesuit and astronomer. A photo of the sundial is reported below. In Italian, the sundial is translated as orologio solare, as written in the image.

The analysis of this sundial gave me the opportunity to introduce the principles used to build it. I also learned a bit more about astronomical calculations. Therefore, I want to share with the reader my findings.

What is a sundial?

The sundial (also called meridian) is a time-measuring device based on the regular rotation of the Earth. The Sun’s apparent position in the sky changes the shadow’s projection cast by the dial. This shadow falls on a surface that has been time marked. As a result, the surface can have different orientations and shapes. The Secchi’s sundial is a vertical type with orientation North-South. The title on the top states this: The Secchi’s sundial shows the real time. It also shows the average time (OROLOGIO SOLARE A TEMPO VERO E MEDIO). The calligraphic text on the bottom indicates the geographic coordinates of the sundial.

The latitude and longitude indicate the location of the bell tower. It is part of the cathedral of Alatri (duomo di Alatri o Basilica di San Paolo). As reference meridian (the prime meridian) was consider the one passing for the city of Rome. In particular, it is the meridian that passes through the Collegio Romano observatory. Secchi was the director there at the time of the sundial’s construction. The international adoption of the prime meridian passing through London was agreed upon during an international geographic conference. This conference was organized in the same city in October 1884. Before this date, country were used to adopt their own prime meridian, usually passing for the capital. So it is not surprising that Sacchi used as reference meridian the one passing for Rome. The Colleggio Romano was a school established by founder of the Society of Jesus St. Ignatius of Loyola in 1551. It is located in the Piazza del Collegio Romano in the Pigna District. P.A. Secchi was the director of the astronomic observatory of the school. The Monte Mario Observatory was constructed in 1934, at Villa Mellini. This moved the prime meridian for Rome there. It was used as the reference meridian for Italy’s geographic maps until 1960.

The geographic coordinates of the cathedral of Alatri given by Google Maps are 41.7248° N, 13.3443° E. Therefore, Sacchi approximated the longitude to the one of the Collegio Romano (41.8988° N, 12.4807° E) that he could accurately calculate. According to Google Earth, the sundial’s position is 41°43′ 35.86″ N, 13° 20′ 33.86″ E. Therefore, the prime meridian is used to calculate the real-time of the sundial.

The length of the shadow cast by the sundial varies with the Sun’s altitude, and it also changes during the year as the Earth moves along an orbit that is inclined by ~23.4° concerning the ecliptic plane (the position of the Sun’s equator). The length defines a particular position for the Earth in its orbit, as the solstices and equinoxes are the dates in between. The length of the shadow is marked on the solar clock with seven declination arcs. The latter ones go from left to right, delimited by the Zodiac signs and solstices, and equinoctial dates. Using the Zodiac sign is a convenient way to divide into 12 sectors of 30° the ecliptic longitude along the Earth’s orbit. This leads to 7 arcs, five crossed twice by the Sun (when its declination is increasing and decreasing), plus two for solstices (extreme declinations). As Sun’s altitude varies between +/- 23° 26′, it is also possible to draw arcs every 5° of declination, with the equinoctial line (March 21st and September 22nd) in the middle which corresponds to 0° of declination (Sun on the equator).

Description of the Components of the Sundial

The Secchi’s sundial in Alatri consists of several key components that contribute to its functionality and accuracy in measuring time. These components include the gnomon, the dial plate, the hour lines, and the declination arcs. The dial plate serves as the surface upon which the shadow of the gnomon falls. It is typically a flat, horizontal surface with markings or engravings that denote the hours of the day. In the case of this sundial, the dial plate features hour lines and declination arcs that aid in reading the time and understanding the position of the Sun.

- Gnomon: The gnomon is a crucial element of the sundial, responsible for casting the shadow that indicates the time. In the case of the Secchi’s sundial, the gnomon is a vertical structure aligned in a North-South direction. It is designed to be perpendicular to the dial plate and is carefully positioned to ensure the accuracy of the shadow projection.

- Hour Lines: The hour lines on a vertical sundial represent the hours of the day and are usually spaced evenly on the dial plate. To determine the position of the hour lines, we consider the angle between the gnomon and the noon line (the line pointing directly towards the Sun at solar noon). Let’s denote this angle as θ. Assuming that the gnomon is aligned perfectly North-South, the angle θ can be calculated using the latitude of the sundial’s location (represented by φ). The equation is as follows:

Once we have the angle

, we can divide it by

(since there are 15 degrees of longitude per hour) to determine the angular distance between each hour line.This angular distance can then be translated into linear distances on the dial plate based on the specific design of the sundial. In Secchi’s sundial, the lines are indicated with Roman numerals from left to right as X, XI, XII, I, II, III, IV, respectively.

- Declination Arcs: The sundial incorporates declination arcs, which are curved lines that represent the lengths of the shadow at specific times of the year. In the case of the Secchi’s sundial, there are seven declination arcs. These arcs are marked by the signs of the Zodiac and the solstices and equinoxes. The declination arcs provide additional reference points for understanding the position of the Sun and the corresponding time. The declination arcs on the sundial represent the lengths of the shadow cast by the gnomon at specific times of the year. The position of these arcs can be determined using the latitude of the sundial’s location and the declination of the Sun at various points throughout the year. The declination (represented by δ) is the angular distance between the Sun and the celestial equator. It varies throughout the year due to the tilt of the Earth’s axis. The formula for calculating the declination at a given day of the year is complex and involves astronomical calculations, but it can be approximated using simpler methods. Using the simplified approximation, we can calculate the declination (δ) based on the day number (represented by n, with n=1 being January 1st). The equation is as follows:

With the declination (\delta) determined, we can mark the corresponding declination arc on the sundial. The length of the arc will depend on the specific design and scale of the sundial.

- Analemmas: The analemmas on a sundial are curves that represent the changing position of the Sun in the sky throughout the year. The shape of the analemma is influenced by the combined effect of the Earth’s elliptical orbit and axial tilt. The equation of time is directly related to the shape and position of the analemmas. The equation of time is a mathematical expression that represents the difference between solar time (based on the Sun’s actual position in the sky) and mean solar time (based on a uniform 24-hour day). This difference arises from two main factors: the Earth’s elliptical orbit and its axial tilt. The equation of time (EoT) is given as a function of the day of the year (n) and is typically measured in minutes. It can be positive or negative, indicating whether solar time is ahead or behind mean solar time, respectively. The equation of time affects the position of the Sun in the sky and, consequently, the position of the hour lines and analemmas on a sundial. The analemmas help to correct the discrepancy between solar time and mean solar time by providing reference points on the sundial.

By combining the gnomon, the dial plate with hour lines, and the declination arcs, the Secchi’s sundial allows for the accurate measurement of time-based on the position and length of the shadow cast by the gnomon. Observers can align the shadow with the hour lines to determine the time of day. At the same time, the declination arcs provide insights into the Sun’s position along the ecliptic throughout the year.

It is worth noting that the accuracy of the sundial’s measurements can be influenced by factors such as the precise alignment of the gnomon, the dial plate’s orientation, and the location’s latitude. However, the design of the Secchi’s sundial, with its North-South alignment and inclusion of declination arcs, enhances its accuracy and usefulness as a time-measuring device in Alatri.