Surfactants are everywhere in protein science — from biochemical laboratories to industrial detergents. Among them, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) is perhaps the most famous (or infamous), widely used for its ability to bind, deactivate, and often denature proteins. Despite decades of experimental and theoretical work, the molecular details of how surfactants bind to protein surfaces are still not fully understood. In my recent study, “Binding Dynamics of Linear Alkyl-sulfates of Different Chain Lengths on a Protein Surface” [1], I have explored this problem using molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, focusing on how the length of the surfactant’s hydrocarbon chain influences protein binding.

Continue readingChlorophyll in Tight Spaces: How Silica Nanoconfinement Stabilizes Photosynthetic Pigments

In a recent molecular dynamics study [1] in collaboration with Prof. K. J. Karki (Department of Physics, Guangdong Technion-Israel Institute of Technology in China), we explored how EthylChlorophyllide a behaves when confined between two silica surfaces — a situation relevant for artificial photosynthesis, nanomaterials, and bio-inspired light-harvesting systems. Chlorophylls are among the most important molecules on Earth. They enable plants, algae, and photosynthetic bacteria to convert sunlight into chemical energy. Yet, outside their natural protein environment, chlorophyll molecules are fragile as they can easily lose their central magnesium ion (demetallation), they degrade under light, and they tend to aggregate uncontrollably in solution.

In natural photosynthetic systems, proteins protect and organize chlorophylls. Reproducing this level of control in artificial systems remains a major challenge. One promising strategy is nanoconfinement — trapping chlorophyll derivatives inside well-defined inorganic structures such as silica nanopores.

Continue readingLook at the Rainbow in a Soap Film: A simple STEM Project

My heart leaps up when I behold

A rainbow in the sky:

So was it when my life began;

So is it now I am a man;

So be it when I shall grow old,

Or let me die!

The Child is father of the Man;

And I could wish my days to be

Bound each to each by natural piety.William Wordsworth, March 26, 1802

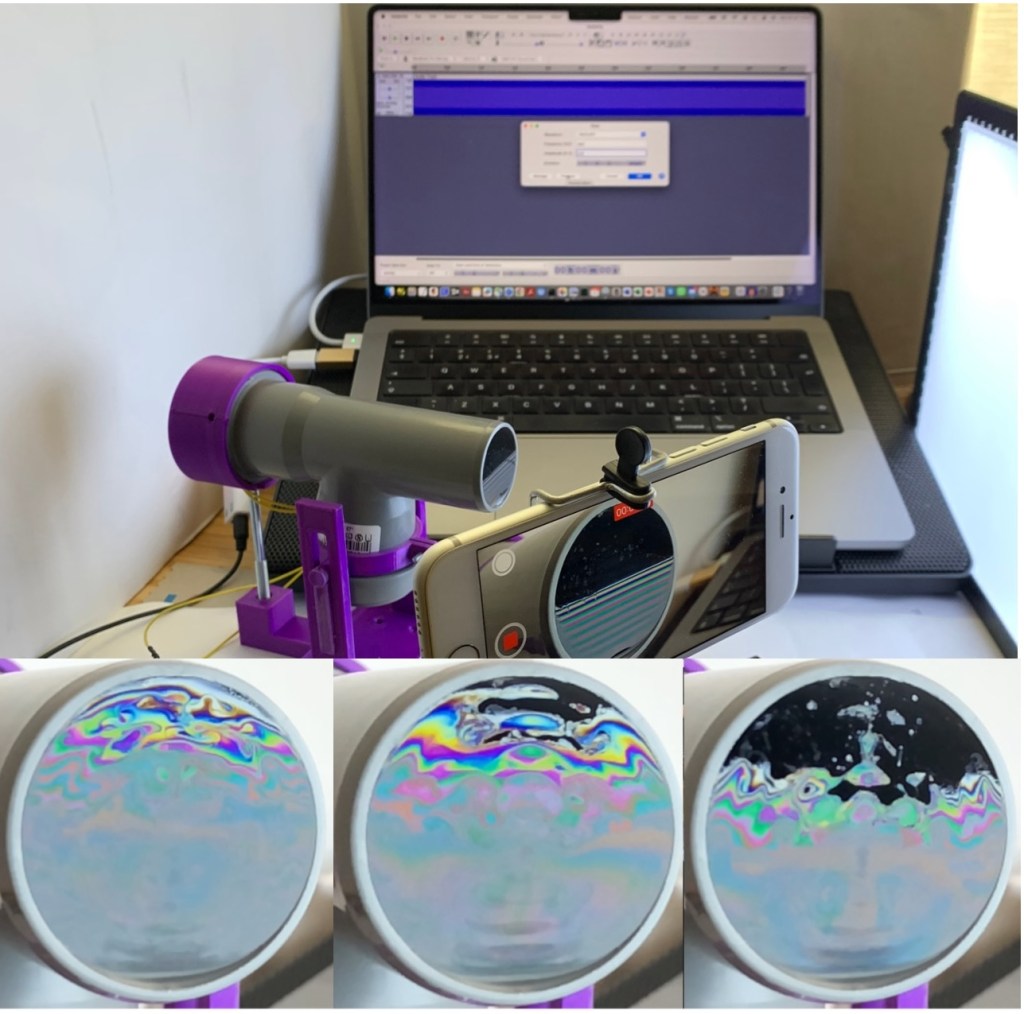

I couldn’t resist citing the beautiful poetry by Wordsworth about the rainbow to introduce my new Instructable, ‘Explore the Physics of Soap Films with the SoapFilmScope.’ I got the idea for this project by reading an article by Gaulon et al. [1]. The authors describe in detail the use of soap film as an educational aid to explore interesting effects in the fluid dynamics of this system. In particular, they examine the impact of acoustic waves on the unique optical properties of the film. In this Instructable, we have designed a device called the SoapFilmScope to perform these experiments. This tutorial will guide you through the process of creating this device, showcasing the mesmerizing interaction between sound waves and liquid membranes. The SoapFilmScope offers an engaging way to explore the physics of acoustics, light interference, and fluid dynamics.

When a sound wave travels through the tube and vibrates the soap film, it creates dynamic patterns through several fascinating mechanisms:

The device consists of a vertical soap film delicately suspended at the end of a tube obtained from a PVC T-shaped fitting that you can get from any DIY store. By attaching a small inexpensive speaker to it, you can let the film dance to the rhythm of the music.

Retro Programming Nostalgia VI: Exploring the Hyperspace

Henk Rogers: Um, I like Pascal. Assembler is my go-to. But never underestimate…

Alexey Pajitnov: …the power of BASIC.

From the movie Tetris (2023).

It has been a long while that I wanted to write this article. The usual motivation is to propose another of my BASIC programming explorations performed in the 80s on my Philips MSX VG-8010 and Amiga 500 microcomputer. The exploration was encouraged by the reading of another of the brilliant articles by A. K. Dewdney in his column “Ricreazioni al Calcolatore” (Computer Recreation) of Le Scienze, the edition in Italian of Scientific American [1]. Dewdney’s article was inspired by the beautiful book by Thomas F. Banchoff [2] who pioneered in the early 1990s the study using computer graphics of hyperdimensional objects.

Continue readingExploring Disordered Proteins: A Study on Flexible Peptides

Proteins are not always rigid structures. Many of their most important parts — linkers, loops, and disordered regions — are highly flexible, constantly changing shape in solution. To understand how these regions behave, scientists often study short model peptides that capture the essential physics of flexibility. In a new article [1], I have explored the behavior of glycine- and serine-rich octapeptides using molecular dynamics simulations combined with concepts from FRET (Förster Resonance Energy Transfer) spectroscopy (see also my previous post).

Continue readingEaster 2024: Dinosaur Eggs, Kinder Surprise, Drug Capsules, Jumping Beans Toy and Retro programming

Oh my God. Do you know what this is? This is a dinosaur egg. The dinosaurs are breeding.

Dr. Alan Grant, Jurassic Park movie (1993)

We are again approaching Easter time and, as tradition, I would like to celebrate with an article dedicated to the most perfect thing in nature: the egg. I came across interesting books about the discovery of dinosaur eggs last year. Dinosaurs are the ancestors of birds and modern reptiles, so we will take a little detour from the traditional Easter egg, and with the spirit of equal opportunity justice, we will look at the shape of these.

Continue readingThe KaleidoPhoneScope: a Dance of Light, Sounds, and Mathematics

Sometime ago, I have written about the Lissajous-Bowditch figures. In the same article, it is described how to build a simple device called a kaleidophone to generate Lissajous patterns. Using a small mirror fixed securely to the end of a bent wire on a stable platform and a laser beam from a laser pointer reflects off it, mesmerizing, intertwined spirals of light. The laser beam will appear dancing on the wall of your room. This enchanting display results from two mutually perpendicular harmonic oscillations generated by the vibrations of the elastic wire. These captivating patterns are known as Lissajous-Bowditch figures and are named after the French physicist Jules Antoine Lissajous, who did a detailed study of them (published in his Mémoire sur l’étude optique des mouvements vibratoires, 1857). The American mathematician Nathaniel Bowditch (1773 – 1838) conducted earlier and independent studies on the same curves, and for this reason, the figures are also called Lissajous-Bowditch curves [2].

LB curves result from the combination of two harmonic motions, and therefore, they can be mathematically generated through a parametric representation involving two sinusoidal functions (see Figure and also here). Lissajous invented different mechanical devices reproducing these periodic oscillations consisting of two mirrors attached to two oriented diapasons (or other oscillators) by double reflecting a collimated ray of light on a screen, producing these figures upon oscillations of the diapasons. The diapason can be substituted with elastic wires, speakers, pendulum, or electronic circuits. In the last case, the light is the electron beam of a cathodic tube (or its digital equivalent) of an oscilloscope [3].

The simplest of these devices is the KaleidoPhone, invented (and named) by the British physicist Charles Wheatstone at the beginning of the 19th century [3,4]. The Kaleidophone creates stunning Lissajous patterns and is an excellent example of how science can also be an art form. You can bring the mesmerizing dance of light to life with just a few simple materials and creativity.

In a new Instructable project, I have presented a modern compact version of the kalidophone device fabricated with the help of 3D printing technology and enhanced with a digital camera.

For this last bit of modern technology, the new device is called KaleidoPhoneScope. What makes this little device is the facility to adapt it to record another form of vibrations by adding a speaker and another mirror free to vibrate on its bizarre pattern, recalling SciFi movies promp appear on a free wall (or door) of your studio.

As Christmas approaches, what is the best time to try this device with a traditional song? Here is the result. Activate the captions to see the corresponding frequencies of the tones.

I wish you all to spend a Merry Christmas with your dearest, and I hope to see a peace and

REFERENCES

- T. B. Greenslade Jr., “All about Lissajous figures,” The Physics Teacher, 31, 364 (1993).

- T. B. Greenslade Jr., “Devices to Illustrate Lissajous Figures,” *The Physics Teacher, 41, 351 (2003).

- C. Wheatstone, Description of the kaleidophone, or phonic kaleidoscope: A new philosophical toy, for the illustration of several interesting and amusing acoustical and optical phenomena, Quarterly Journal of Science, Literature and Art 23, 344 (1827).

- R. J. Whitaker, “The Wheatstone kaleidophone,” American Journal of Physics, 61, 722 (1993).

Crystallographic Coordinates

Atomic Fractional Coordinates

Atomic fractional coordinates (AFCs) are used to specify the positions of atoms within a crystal structure. They are expressed as three fractional values that represent the relative positions of atoms within the unit cell of the crystal. If

are the cartesian coordinate an the atom in a cubic lattice of lattice parameters

, the ACF are calculates as

therefore, the value of ACFs are fractional values between 0 and 1. For example, an atom at (0.25, 0.5, 0.75) is located a quarter of the way along the a-axis, halfway along the b-axis, and three-quarters of the way along the c-axis of the unit cell. Crystal structures often exhibit symmetry, and fractional coordinates are essential for understanding and describing this symmetry. Symmetry operations, such as rotations, translations, and reflections, can be applied to fractional coordinates to elucidate the symmetrical aspects of the crystal, which is crucial for understanding the material’s properties.

Continue readingEl cálculo de la constante de Madelung

To all the Spanish-speaking readers, this is an AI-assisted translation experiment using WordPress. Please bear with me as my knowledge of the Spanish language is limited, so I cannot detect possible incorrect translations of the original test in Italiano. If you appreciate my efforts, please let me know. If you notice any errors in the translation, please send me a message to correct them. You can find my original versions in English, Italian, and German language of this text by clicking the links.

Estimados lectores de habla hispana, este es un experimento de traducción asistida por IA utilizando WordPress. Les pido paciencia ya que mi conocimiento del idioma español es limitado, por lo que no puedo detectar posibles traducciones incorrectas del texto original en italiano. Si aprecian mis esfuerzos, por favor háganmelo saber. Si notan algún error en la traducción, por favor envíenme un mensaje para corregirlo. Pueden encontrar las versiones originales en inglés, italiano y alemán de este texto haciendo clic en los enlaces.

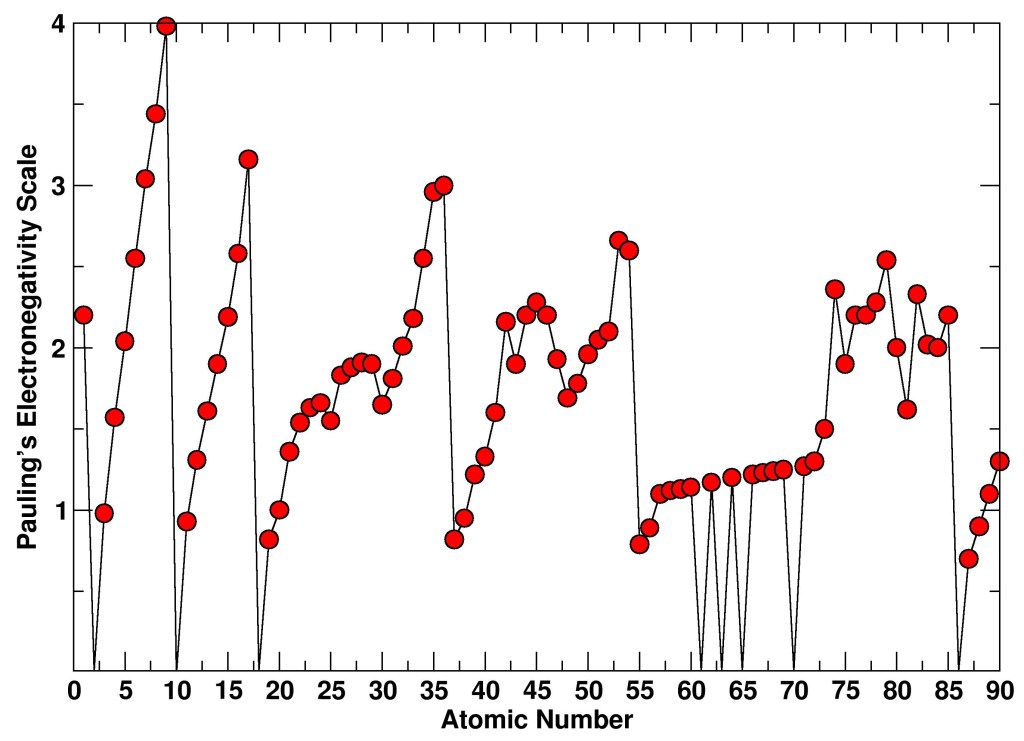

Continue readingMethods of Calculating Atomic Charges based on Electronegativity. Part I.

The electronegativity of a chemical element measures the tendency of an atom to attract electrons around it. This definition was formalized for the first time, in a semi-empirical form, by the chemist Linus Pauling in the early 1930s, but it had already been proposed in the late 1800s by the Swedish chemist Berzelius. In molecules, this tendency determines the molecular electronic distribution and therefore influences molecular properties such as the distribution of partial charges and chemical reactivity. Pauling provided an electronegativity scale by comparing bond dissociation energies of pairs of atoms (A, B) using the equation

With $E_{AB}$, $E_{AA}$, and $E_{BB}$ being the dissociation energies of the molecules AB, AA, and BB, respectively.

A few years later, in 1934, Mulliken proposed an expanded definition of electronegativity based on spectroscopically measurable atomic properties such as ionization potential (I) and electron affinity (E):