To grass, or leaf, or fruit, or wall,

The snail sticks close, nor fears to fall,

As if he grew there, house and all

Together.

Within that house secure he hides,

When danger imminent betides

Of storm, or other harm besides

Of weather.

Give but his horns the slightest touch,

His self-collecting power is such,

He shrinks into his house, with much

Displeasure.

Where’er he dwells, he dwells alone,

Except himself has chattels none,

Well satisfied to be his own

Whole treasure.

Thus, hermit-like, his life he leads,

Nor partner of his banquet needs,

And if he meets one, only feeds

The faster.

Who seeks him must be worse than blind,

(He and his house are so combin’d)

If, finding it, he fails to find

Its master.The Snail by William Cowper (1731-1800)

Introduzione

The beautiful poetry of Cowper expresses the pleasant charm that this small inhabitant of our gardens instills. I have always been fascinated by this gastropod, to the point that it was one of my favorite invertebrates for my amateur naturalistic observations. Furthermore, I still recall with pleasure and nostalgia the collection of those called ‘ciammaruchelle‘ in the Ciociaro dialect, which are small snails. These were gathered by the handful in the wheat fields after the harvest. It was one of the various culinary traditions that involved my entire family every year and were carried out with constant devotion. The collection was organized with careful timing, locations, and weather conditions to increase the likelihood of success. Usually, we would return home with a rich and tasty haul, but not without difficulties, as the little snails would climb onto the thistle plants (Cynara cardunculus L., 1753) where they would hide among the thorns to protect themselves from predators. Unfortunately for them, the predator Homo Sapiens Sapiens Frusinenses, equipped with keen eyesight and great tenacity, did not easily give up its prey!

The collected species was a variety of the snail Eobania vermiculata, commonly known as “rigatella,” which is very common in Mediterranean regions. The snails were gathered in woven baskets and, once back home, they were enclosed in circular cages with fine mesh walls for several days to purge their intestines. They were then cooked for a few hours in a tomato base spiced with mint (Clinopodium nepeta), following an ancient recipe. The dish was consumed with fresh or, even better, baked bread to make it crispy. It was a vibrant celebration of scents, flavors, and colors, with the sound of slurping as they tried to empty the succulent contents of their shells. A delicate feast of aromas and flavors: the scent of tomato infused with snail meat and mint, combined with the red color of the snails’ shells adorned with white-brown stripes.

Over time, I have learned that gastropods are the subject of fascinating neurobiology, embryology, and morphology studies. And it is the shell that was the focus of my early studies on the body of these small animals.

I have been interested in studying the physiology of the formation and regeneration of the shell of the Helix Pomatia, another common species in Italy but larger than E. vermiculata. I will discuss this aspect further in another article. In this one, I will focus more specifically on the shape of the shell of this snail species.

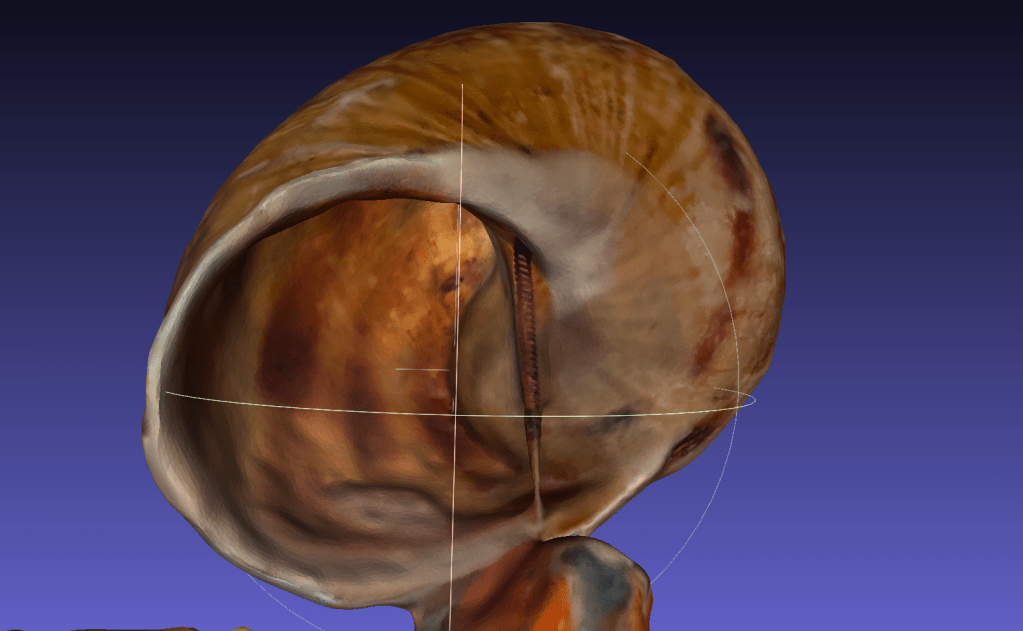

The shape of a snail’s shell can be described using the mathematical model proposed by Cortie, as I described in a recent article. But how accurately does the model reproduce the shape of a natural shell? To verify this, we can compare the mathematical model with one obtained from a three-dimensional digitization of natural shells.

The digitization of the snail shell

Recently, I had the opportunity to collect various snail shells in the garden of my family’s house in Italy which I analyzed using structure-from-motion (SfM) photogrammetry algorithm. This algorithm allows converting photos of an object, taken from different angles, into a three-dimensional model of the object itself. I used an Apple MacBook with an Arm M1 processor and 16 GB of RAM as hardware, and the software PhotoCatch and MeshLab. Many years ago, I found an empty shell of a Helix aspersa maxima in the garden of my home. The shell not only shows the signs of the troubled life of this small animal but also the evidence of a tragedy that happened to the occupants of the empty shell.

Principle of Structure-from-Motion (SfM) Photogrammetry Algorithm with Mathematical Details

Photogrammetry based on the Structure-from-Motion (SfM) algorithm is a sophisticated method for reconstructing three-dimensional models using a series of two-dimensional images. This approach leverages the principles of projective geometry and stereoscopic vision to estimate the 3D structure of an object or environment. The main goal of SfM is to estimate the 3D position of the cameras used to capture the images, as well as the 3D structure of the object or scene itself. The SfM algorithm relies on a series of mathematical steps to estimate the camera positions and the 3D structure of the object. Here is an overview of the main steps involved:

- The first step in SfM reconstruction is to identify key points in each image. Each point is represented as a vector in three-dimensional space (X, Y, Z). The goal is to accurately estimate the 3D coordinates of these points.

- Each camera has intrinsic parameters, such as focal length, distortion, and scale factor. These parameters need to be calibrated to achieve accurate results in 3D reconstruction. Some parameters, such as Exif (Exchangeable Image File Format) data, can be embedded as metadata in the photos themselves. However, the estimation of intrinsic parameters is mainly based on image analysis rather than solely relying on Exif data.

- Each image captured by the camera has its extrinsic parameters such as position (X, Y, Z) and orientation (rotation and tilt angles). These parameters define the camera’s position in three-dimensional space.

- SfM algorithms search for correspondences between key features in different images. These features are usually interest points such as corners or distinctive points on the object. The correspondences establish relationships between different cameras and the 3D points.

This is a schematic description of the SfM algorithm. Its practical implementation requires specific techniques and methodologies to handle challenges such as matching ambiguity, measurement error, presence of outlier points, camera calibration, etc.

However, there are several programs available, many of which are free and available for different operating systems, that automatically perform this process.

RESULTS OF DIGITIZATION

This photo shows how the sample was prepared for the photoshoot. Plasticine and an acupuncture needle were used to suspend the shell so that 360-degree photos could be taken all around it.

The design printed on the sheet at the base of the playdough ball was taken from the Simple 3D Scanner project by DSB007 on Thingiverse.com, and it is used to provide a background with reference marks for the 3D reconstruction. The software on my MacBook M1 for the SfM reconstruction is the freeware for MacOSX called PhotoCatch. I used around 160 photos taken using an iPhone 8, resulting in a high-resolution model.

A body of inclusion has been observed near the opening of the snail’s shell (in the blue circle in the first photo of the series). What is buried inside the visible calcareous bubble in the photo is unclear. It is likely to be a tiny piece of a leaf or a blade of grass that the animal could not free itself from, and therefore, as a form of defense, it has coated it with the secretion used to build the shell.

Moreover, as shown in the above figure, the shell concealed another secret fully revealed when I accidentally broke a piece of the shell. After the snail’s death, the shell was first used as a refuge for a family of groundhogs. Unfortunately, it seems that it also became their grave. Judging from the orderly state of the group of individuals, I gather that the tragedy occurred during their winter hibernation, from which they never woke up.

As you can see in the previous image, the shape of the insect bodies has not been reconstructed due to the lack of detailed photos with sufficient magnification to achieve this level of detail.

In the photo, you can also notice that the 3D reconstruction presents various artifacts on the shell’s surface. Upon closer inspection of the photos used by PhotoCatch, I noticed the presence of some blurry photos that were likely not used by the program. Additionally, it is possible that slight movement of the shell, due to the precarious nature of the support, contributed to these inaccuracies.

However, I am delighted with the overall quality achieved considering the limited resources used and the little attention paid to the collection of photos!