What is the origin of the urge, the fascination that drives physicists, mathematicians, and presumably other scientists as well? Psychoanalysis suggests that it is sexual curiosity. You start by asking where little babies come from, one thing leads to another, and you find yourself preparing nitroglycerine or solving differential equations. This explanation is somewhat irritating, and therefore probably basically correct. David Ruelle, in Chance and Chaos

Here I am again for a new appointment with the Italian version of the column “Retro Programming Nostalgia“, my very own adventure in computer archaeology, rediscovering old programs written some time ago on microcomputers that have made their mark on an era.

This time, in my old floppy disks for the glorious Amiga 500, I found a program in Amiga Basic that I wrote during the early years of my university studies, when I was taking the course on differential equations II. Specifically, I was very fascinated by autonomous systems of differential equations due to their numerous applications in mathematical modeling of physical, chemical, and biological systems, as well as their importance in the theory of chaos. As in the series articles, I want to release an adapted version for the QB64 BASIC meta-compiler, but before presenting the program, I want to briefly explain what an autonomous system of differential equations is.

Autonomous systems of differential equations

In mathematics, an “autonomous” system of differential equations is defined as one that does not explicitly depend on time. If the system depends only on two dependent variables (or state variables), it is also called a “plane” because the solutions of these variables can be visualized on a two-dimensional plane.

Mathematically, such an autonomous system is defined as:

Given x and y as the state variables and the derivatives and

as their rates of change concerning the independent variable t. The functions

and

determine the relationships between the derivatives and the state variables. These functions can depend linearly or nonlinearly on x and y (or simply be constants), but they do not explicitly involve the independent variable (t).

The behavior of such a system can be extremely fascinating and diverse, ranging from stable equilibrium points to periodic orbits, chaotic behavior, and more. Mathematicians and scientists often use graphical techniques and analytical methods to study the properties and solutions of autonomous planar systems, gaining insights into their long-term behavior. These systems find applications in various fields, including physics, engineering, biology, and economics, for modeling and understanding the dynamics of various real-world phenomena. In general, autonomous systems of ordinary differential equations are essential tools in the study of dynamical systems (time-dependent) and provide valuable insights into the evolution of complex physical systems over time.

Let’s delve deeper into the topic by exploring the so-called critical points and the types of solutions of these systems.

Critical Points (Equilibrium Points)

In an autonomous planar system, critical points, also known as equilibrium points or fixed points, are the points where the derivatives of both state variables with respect to time are equal to zero. Mathematically, for a system with state variables x and y, critical points are found by simultaneously solving the following equations:

Critical points represent states where the system is in a stationary state, which means that the state variables do not change over time. These points are crucial as they reveal stable, unstable, or semi-stable behaviors of the system. The behavior around critical points can be determined by analyzing the eigenvalues of the Jacobian matrix of the system evaluated at those points.

Analysis of the phase plane

To gain a deeper understanding of the behaviour of an autonomous planar system, phase plane analysis is commonly used. The phase plane represents the trajectories of the system in the state space (plane). Each axis represents one of the state variables, and the trajectories are represented as curves on this plane.

By plotting critical points and analyzing their stability properties, as well as drawing some typical trajectories, one can visualize the overall behavior of the system and identify important features such as limit cycles, fixed points, and complex dynamics.

In summary, autonomous systems of planar differential equations play a crucial role in understanding the dynamics of various real-world systems. By studying critical points and analyzing solutions, mathematicians and scientists can gain insights into the long-term behaviour of these systems, helping them make predictions and draw conclusions about the phenomena they represent.

Autonomous systems of planar differential equations exhibit various fascinating behaviours, making them an affluent area of study for mathematicians and scientists. Here are some insights into the different types of behaviours observed in such systems.

- Stable Equilibrium Points: A stable equilibrium point, also known as an attractor, represents a state where the system tends to stabilize over time. If the trajectories of the system start near a stable equilibrium point, they will converge towards it as time passes. Such points are important for understanding the steady-state behavior of the system and can correspond to stable states in physical systems, such as the resting position of a pendulum or the equilibrium point of a chemical reaction.

- Unstable Equilibrium Points: An unstable equilibrium point, also called a repellor, represents a state where the system is highly sensitive to perturbations. Trajectories starting near an unstable point quickly diverge from it over time. These points often correspond to unstable or critical conditions in real systems.

- Saddle Points: A saddle point is a special type of critical point that exhibits stable and unstable behaviors along different directions in state space. Trajectories near a saddle point approach it in one direction and diverge in the other. Saddle points are interesting because they represent a combination of stability and instability, and their presence can lead to complex dynamics in the system.

- Limit Cycles: A limit cycle is a closed trajectory in phase space that the system repetitively follows without approaching a critical point. These cycles correspond to periodic or oscillatory behavior in the system. Limit cycles can be stable, leading to regular and predictable oscillations, or unstable, resulting in non-repetitive or chaotic oscillations.

Overall, the study of autonomous systems of ordinary differential equations is a fascinating and interdisciplinary field that combines mathematical analysis, numerical methods, and graphical techniques. Understanding the behaviors and properties of these systems helps scientists and engineers comprehend the dynamics of complex phenomena, design control strategies, and make predictions about real-world processes. The interplay between stability, periodicity, chaos, and bifurcations makes this research area both stimulating and rewarding, with numerous applications in various scientific disciplines.

The Solutions (Trajectories in Phase Space)

The solutions of an autonomous planar system are the curves that describe how the state variables evolve over time. Solving such systems is not always simple, and analytical solutions may not exist for all cases. However, numerical methods like the Euler method or the Runge-Kutta method can approximate the solutions numerically. There are different types of solutions or trajectories that the system can exhibit:

- Stable solutions: If nearby trajectories converge to a critical point over time, the critical point is considered stable. The system tends to return to this state after small perturbations.

- Unstable solutions: If nearby trajectories diverge from a critical point, the critical point is unstable. Even small perturbations can push the system away from this state.

- Semi-stable solutions: A semi-stable critical point can exhibit stable behavior in one direction and unstable behavior in another direction.

- Limit cycles: These are closed and periodic trajectories that the system follows indefinitely without approaching a critical point. Limit cycles often represent periodic or oscillatory behavior in the system.

- Chaos: In some cases, the system can exhibit chaotic behaviour, where trajectories are highly sensitive to initial conditions, resulting in unpredictable and non-repetitive patterns.

STUDY OF AN AUTONOMOUS LINEAR PLANE SYSTEM

Let’s consider the planar autonomous system:

where a, b, c, and d are constants.

To perform a phase plane analysis, we will find the critical points and classify their stability, then plot some typical trajectories to visualise the system’s behaviour.

Finding Critical Points

Critical points are found by setting the derivatives dx/dt and dy/dt equal to zero:

To find the critical points , we solve the system of equations. Let’s assume

to avoid degenerate cases:

From the first equation, we can isolate y:

Now, substitute this value of y in the second equation:

Subsequently, isolate x.

So, we have two critical points:

(assumendo che

)

Using the equation $y = -(a/b) x$, we can find the corresponding values of y for these critical points:

Stability Analysis

To analyze the stability of critical points, it is necessary to calculate the Jacobian matrix evaluated at each critical point. The Jacobian matrix for the two-dimensional system is:

Where ∂ represents the partial derivative. In this case, the behavior of the system is summarized in the graph of the determinant with respect to the trace of J.

In the case of the linear autonomous systems considered in the previous paragraph, the Jacobian is defined as:

Now, let’s evaluate the Jacobian matrix at each critical point:

- At (0, 0):

- At (b/d, -a/d):

Representation and Classification of Trajectories in Phase Space

We have reached the point where the use of a computer program can be very helpful in visualizing the solutions of these systems. To draw some typical trajectories and visualize the behavior of the system in the phase plane, we can first identify the critical points (0, 0) and (b/d, -a/d), and then draw representative trajectories through different initial conditions.

The direction of the trajectories can be determined by the signs of and

For example, if

and

at a certain point

then the trajectory points towards the upper right quadrant.

The actual shape and behavior of the trajectories depend on the specific values of a, b, c, and d. By analyzing the stability of the critical points, we can deduce whether the trajectories converge towards or diverge from these points.

The classification of solutions in an autonomous system of planar differential equations involves understanding the behavior of the trajectories around the critical points. The classification is based on the stability properties of these critical points, which can be classified into three main categories:

Stable Critical Points (Attractors):

A critical point is considered stable if trajectories starting in its vicinity converge towards the critical point over time. In other words, if a small perturbation (initial deviation) is introduced to the state variables (x, y) around the critical point, the trajectories will eventually approach and remain close to the critical point. Stable critical points are often associated with stable and predictable behavior in the system. For example, in the context of a mechanical system, a stable critical point might represent the equilibrium position where the system settles when undisturbed.

Unstable Critical Points (Repellers):

A critical point is considered unstable if trajectories starting in its vicinity move away from the critical point as time progresses. In this case, small perturbations to the state variables cause the trajectories to diverge further from the critical point. Unstable critical points represent unstable states or conditions in the system. For example, in a mechanical system, an unstable critical point could correspond to the position of an inverted pendulum, where the slightest disturbance leads to a collapse.

Saddle points:

A saddle point is a special type of critical point that exhibits stable and unstable behaviors along different directions in state space. Trajectories near a saddle point approach the critical point along one direction (stable) and move away from it along another direction (unstable). Saddle points are characterized by having at least one positive eigenvalue and one negative eigenvalue in their matrix.

In a two-dimensional autonomous system of differential equations of the form:

The characteristics of the system’s solutions depend on the properties of the coefficient matrix ( ). In particular, various types of solutions can be obtained based on the trace and determinant of this matrix, namely Tr=(a+b) and Det=(ad-bc).

Classification of Solutions Based on the Coefficient Matrix

- A. Positive Determinant and Trace ((ad – bc > 0) and (a + d > 0)):

- This indicates that the matrix has two real eigenvalues with opposite signs. The solutions of the system converge to a stable point at the origin (an asymptotically stable equilibrium point).

B. Negative Determinant and Trace ((ad – bc > 0) and (a + d < 0)):

- The matrix has two real eigenvalues with opposite signs. The solutions of the system converge to a stable point at the origin (an asymptotically stable equilibrium point), but follow oscillating trajectories.

C. Positive Determinant, Negative Trace ((ad – bc > 0) and (a + d < 0)):

- The matrix has two complex eigenvalues with negative real part. The solutions of the system converge to a stable point at the origin, following oscillating trajectories.

D. Zero Determinant ((ad – bc = 0)):

- In this case, the matrix has one double real eigenvalue or two coincident eigenvalues. The solutions can be linear or exhibit special behaviors, such as radial or circular trajectories.

E. Negative Determinant ((ad – bc < 0)):

- The matrix has two complex eigenvalues with non-zero real part. The solutions follow spiral trajectories, approaching or moving away from a stable point at the origin depending on the sign of the real part of the eigenvalues.

- Zero Determinant or Multiple Eigenvalues: When the determinant is zero or there are multiple eigenvalues, the solutions can exhibit more complex behaviors. In these cases, additional details, such as eigenvalue and eigenvector analysis, need to be considered to determine the exact behavior of the system.

In the Appendix, I have included the program I mentioned at the beginning of the article. The program is a modified and enhanced version of the QB64 BASIC compiler. It allows you to change the parameters and by clicking on the graph, obtain solutions for initial values of (x0, y0). It is also possible to scan along the x and y axes to automatically generate a set of evenly spaced curves.

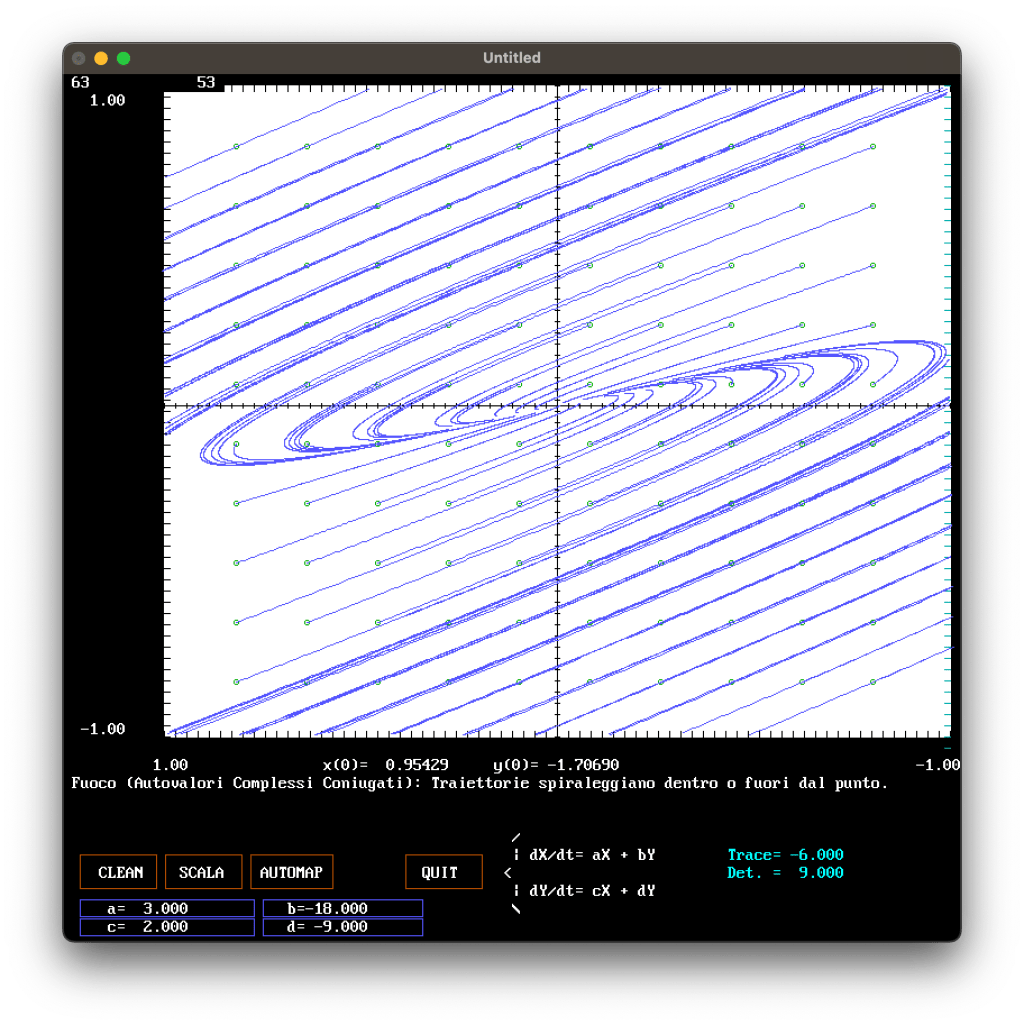

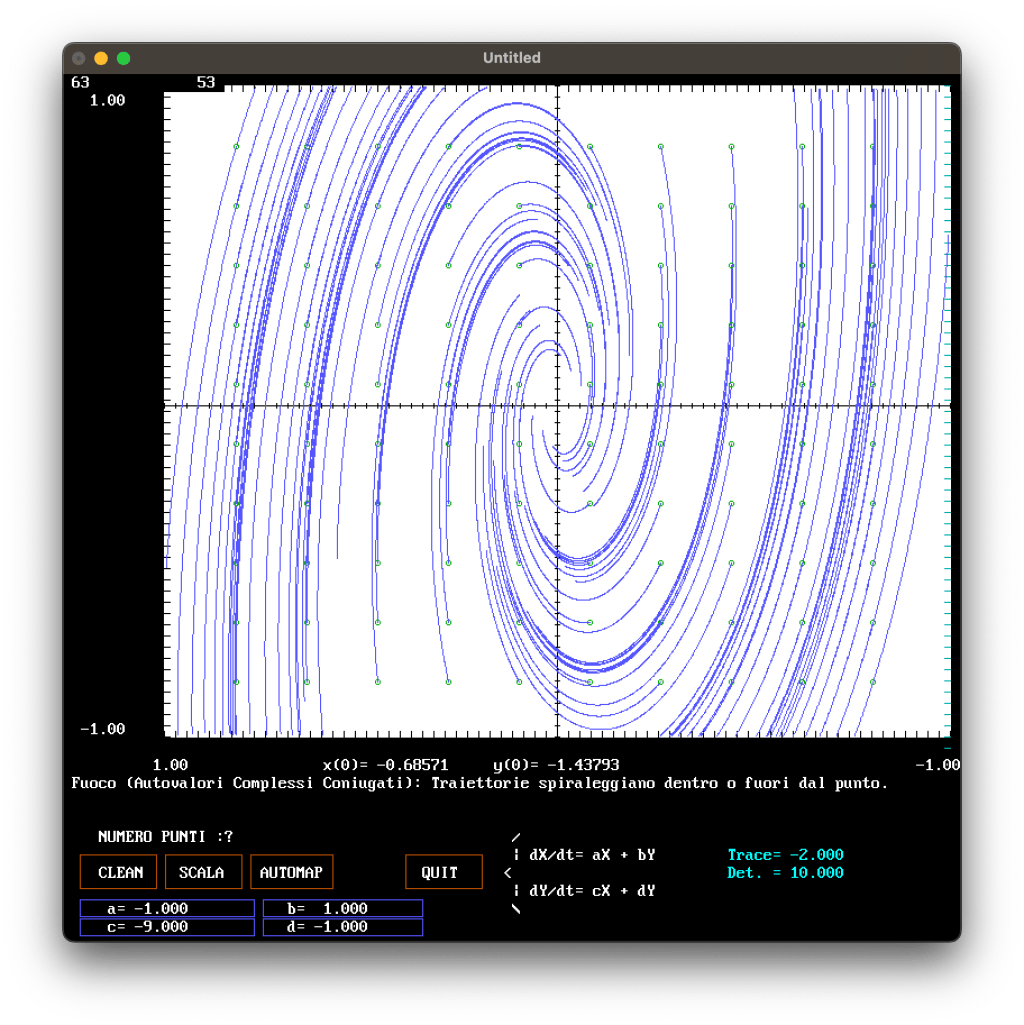

The following figures show some examples of phase plane representations for different systems.

APPENDIX

The QB64 Basic program (Qbasis) for studying a linear autonomous ordinary differential equation system. This program is an interactive tool to visualize and analyze the behavior of solutions of a system of linear ordinary differential equations. Users can adjust the system parameters, run simulations, and obtain information about the classification of critical points.

Here is a brief description of the main parts of the program:

DISEGNA_INTER:

- This subroutine draws a graphical interface to display the system of differential equations.

- It draws Cartesian axes, guidelines, and provides information about the scale and parameters of the system.

- Based on the values of the coefficients

a,b,c, andd, it classifies the behavior of the critical point of the system.

ClassifyCriticalPoint:

- This subroutine is called by

DISEGNA_INTERto classify the critical point of the system based on the values of trace (Tr) and determinant (Det) of the coefficient matrix. - It provides a textual description of the type of critical point and prints the values of trace and determinant.

MAIN:

- The main subroutine of the program handles user interaction and mouse control.

- It allows the user to modify the system parameters, clear the graph, adjust the scale, and perform a simulation of the system trajectories.

INTEGRAZIONE_EUL:

- This subroutine performs numerical integration of the differential equations using the Euler’s method.

- It calculates and plots the trajectories on the graph based on the system parameters and mouse position.

Please read the terms of use of the program in this link.

''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''

' STUDIO DEL SISTEMA DI EQUAZIONI DIFFERENZIALI

' AUTONOMO PIANO LINEARE

'

' | dX/dt= aX + bY "

' <

' | dY/dt= cX + dY "

'

' VERSIONE: 1.1 '

'

' AUTORE: (C) DANILO ROCCATANO

' PRIMA VERSIONE: 1993

' REVISIONE: 2023

''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''

Screen _NewImage(800, 800, 256)

Dim Shared a, b, c, d, dx, dy As Double

Dim Shared h As Double

Dim Shared pa, PX, PY, CL As Integer

Dim Shared EINFX, ESUPX, EINFY, ESUPY As Double

a = 1

b = 2

c = 3

d = 1

' Limiti iniziali del grafico

EINFX = -1.

ESUPX = 1.0

EINFY = -1.0

ESUPY = 1.0

Cls

DISEGNA_INTER

MAIN

Sub INPUT_PAR

Shared a, b, c, d, dx, dy

Shared h

Shared pa, PX, PY

Dim pp As Double

Locate 43, 5: Input "INSERISCI PARAMETRO:"; pp

If pa = 1 Then a = pp

If pa = 2 Then b = pp

If pa = 7 Then c = pp

If pa = 8 Then d = pp

pa = 0

Cls

DISEGNA_INTER

End Sub

Sub DISEGNA_INTER

Shared a, b, c, d, dx, dy

Shared h

Shared pa

Line (90, 10)-(790, 590), 3, B

Line (90, 10)-(790, 590), 15, BF

Line (440, 10)-(440, 610), 0

Line (90, 295)-(790, 295), 0

For T = 0 To 80

Line (90 + 10 * T, 293)-(90 + 10 * T, 297), 0

Line (90 + 10 * T, 10)-(90 + 10 * T, 15), 0

Line (90 + 10 * T, 585)-(90 + 10 * T, 590), 0

Next T

For T = 0 To 60

Line (90, 10 + 10 * T)-(95, 10 + 10 * T), 0

Line (438, 10 + 10 * T)-(442, 10 + 10 * T), 0

Line (785, 10 + 10 * T)-(790, 10 + 10 * T), 3

Next T

Locate 2, 2: Print Using "###.##"; ESUPY

Locate 37, 2: Print Using "###.##"; EINFY

Locate 39, 9: Print Using "###.##"; ESUPX

Locate 39, 95: Print Using "###.##"; EINFX

' MENU DEI COMMANDI

Locate 45, 4: Print " CLEAN "

Locate 45, 12: Print " SCALA "

Locate 45, 22: Print " AUTOMAP"

Locate 45, 40: Print " QUIT "

Line (15, 695)-(83, 725), 6, B

Line (91, 695)-(159, 725), 6, B

Line (167, 695)-(240, 725), 6, B

Line (305, 695)-(373, 725), 6, B

Locate 43, 50: Print " /"

Locate 44, 50: Print " | dX/dt= aX + bY "

Locate 45, 50: Print "< "

Locate 46, 50: Print " | dY/dt= cX + dY "

Locate 47, 50: Print " "

Locate 47, 5: Print " a= b= "

Locate 48, 5: Print " c= d= "

Locate 47, 8: Print ; Using "##.###"; a

Locate 47, 28: Print ; Using "##.###"; b

Line (15, 735)-(170, 750), 9, B

Line (178, 735)-(320, 750), 9, B

Locate 48, 8: Print ; Using "##.###"; c

Locate 48, 28: Print ; Using "##.###"; d

Line (15, 752)-(170, 767), 9, B

Line (178, 752)-(320, 767), 9, B

Tr = a + d

Det = a * d - b * c

' Classify the critical point

ClassifyCriticalPoint Tr, Det

End Sub

' Subroutine per classificare le solutzioni e punti critici sulla base della traccia e del determinante

' della matrice dei coefficienti.

Sub ClassifyCriticalPoint (T, D)

If T > 0 And D > 0 Then

TEXT$ = "Nodo (Autovalori Reali Distinti): Traiettorie convergono (Stabile o Instabile)."

ElseIf T > 0 And D < 0 Then

TEXT$ = "Punto di Sella (Autovalori Reali Distinti): Traiettorie si avvicinano in una direzione e si allontanano in un'altra (Instabile)."

ElseIf T < 0 And D > 0 Then

TEXT$ = "Fuoco (Autovalori Complessi Coniugati): Traiettorie spiraleggiano dentro o fuori dal punto."

ElseIf T = 0 And D > 0 Then

TEXT$ = "Centro (Autovalori Complessi Coniugati): Traiettorie formano orbite chiuse."

ElseIf T = 0 And D = 0 Then

TEXT$ = "Centro (Autovalori Complessi Coniugati): Traiettorie formano orbite chiuse."

ElseIf T = 0 And D > 0 Then

TEXT$ = "Nodo o Stella Degenerati (Autovalori Reali Distinti): Traiettorie convergono o si allontanano."

ElseIf T = 0 And D < 0 Then

TEXT$ = "Punto di Sella Degenerato (Autovalori Reali Distinti): Traiettorie si avvicinano in una direzione e si allontanano in un'altra (piu' lentamente rispetto a un punto di sella regolare)."

Else

TEXT$ = "Imprevedibile (Autovalori Complessi Coniugati): Il comportamento puo' essere imprevedibile, coinvolgendo oscillazioni complesse o caos."

End If

Locate 40, 2: Print TEXT$

Color 11: Locate 44, 75: Print ; Using "Trace=###.###"; Tr

Locate 45, 75: Print ; Using "Det. =###.###"; Det

End Sub

Sub MAIN

Shared a, b, c, d, dx, dy

Shared h

Shared pa, PX, PY, CL As Integer

'x-y range

DELTAX = ESUPX - EINFX

DELTAY = ESUPY - EINFY

'integration step

h = 0.01

fs = 1

' risoluzione

dx = DELTAX / 700

dy = DELTAY / 580

' Controllo del mouse

Do

Do While _MouseInput

ta = _MouseButton(1)

mx = _MouseX

my = _MouseY

' Posizione relativa del pixel

X0 = (mx - 400) * dx

Y0 = (295 - my) * dy

'Coordinate cartesiane della posizione del puntatore

Locate 39, 30: Print Using "x(0)=###.##### y(0)=###.#####"; X0, Y0

If (ta And my <= 590 And mx >= 90 And mx <= 790) Then

PX = mx

PY = my

CL = 6

INTEGRAZIONE_EUL

ta = 0

End If

'Controlla se il mouse si trova nella prima linea dei parametri

If (ta And my >= 735 And my <= 750) Then

If (mx >= 15 And mx <= 170) Then pa = 1

If (mx >= 178 And mx <= 320) Then pa = 2

INPUT_PAR

ta = 0

End If

If (ta And my >= 752 And my <= 767) Then

If (mx >= 15 And mx <= 170) Then pa = 7

If (mx >= 178 And mx <= 320) Then pa = 8

INPUT_PAR

ta = 0

End If

Line (15, 695)-(83, 725), 6, B

Line (91, 695)-(159, 725), 6, B

Line (167, 695)-(240, 725), 6, B

If (ta And my >= 695 And my <= 734) Then

ky$ = "0"

If (mx >= 15 And mx <= 83) Then ky$ = "1"

If (mx >= 91 And mx <= 159) Then ky$ = "2"

If (mx >= 167 And mx <= 240) Then ky$ = "3"

If (mx >= 305 And mx <= 373) Then ky$ = "4"

Select Case ky$

Case "1"

Cls

DISEGNA_INTER

Case "2"

KK = fs

Locate 43, 5: Input "Fattore di scala:"; fs

If sf < 0 Then

fs = KK

End If

If KK <> fs Then

Cls

DISEGNA_INTER

End If

EINFX = EINFX * fs

ESUPX = ESUPX * fs

EINFY = EINFY * fs

ESUPY = ESUPY * fs

DELTAX = ESUPX - EINFX

DELTAY = ESUPY - EINFY

Locate 43, 5: Print Space$(40)

Case "3"

Locate 43, 5: Input "NUMERO PUNTI :"; PUNTI%

Locate 43, 5: Print Space$(40)

' Curve campionate lungo X in verde

CL = 2

For T = 0 To PUNTI%

PX = (700 / PUNTI%) * T

PY = 295

INTEGRAZIONE_EUL

Next T

' Curve campionate lungo Y in blue

CL = 9

For T = 0 To PUNTI%

PX = 440

PY = (590 / PUNTI%) * T

INTEGRAZIONE_EUL

Next T

ta = 0

Case "4"

End

End Select

ta = 0

End If

Loop

Loop

End Sub

Sub INTEGRAZIONE_EUL

Shared a, b, c, d, dx, dy As Double

Shared h

Shared pa, PX, PY, CL As Integer

PSet (PX, PY), CL

mx = PX - 440

my = 295 - PY

X0 = mx * dx

Y0 = my * dy

jj = 1

XP = X0

YP = Y0

nn = 0

Do While nn < 701

' Sistema

INX = jj * h * (a * XP + b * YP)

INY = jj * h * (b * XP + c * YP)

X = XP + INX

Y = YP + INY

XP = X

YP = Y

PX = X / dx + 440

PY = 295 - Y / dy

If (PX >= 790 Or PX <= 90) Or (PY <= 10 Or PY >= 590) Then

If jj = 1 Then

jj = -1

X = X0

Y = Y0

PSet (PX, PY), CL

Else

jj = 1

Exit Sub

End If

End If

Locate 39, 30: Print Using "x= ###.##### y= ###.#####"; X0, Y0

Line -(PX, PY), CL

nn = nn + 1

Loop

End Sub