Christmas is a time for traditions, decorations, and—at least for some of us—quiet moments spent playing with ideas. In that spirit, this post is a small seasonal diversion: a recreational exploration of large factorial numbers, their historical computation, and an unusual way to see them. The inspiration comes from an old but delightful article by the great recreational mathematician Martin Gardner, titled “In which a computer prints out mammoth polygonal factorials” (Scientific American, August 1967), in which he discusses the astonishing growth of the function

and the surprising difficulty computers once faced when trying to compute it for even modest values of n.

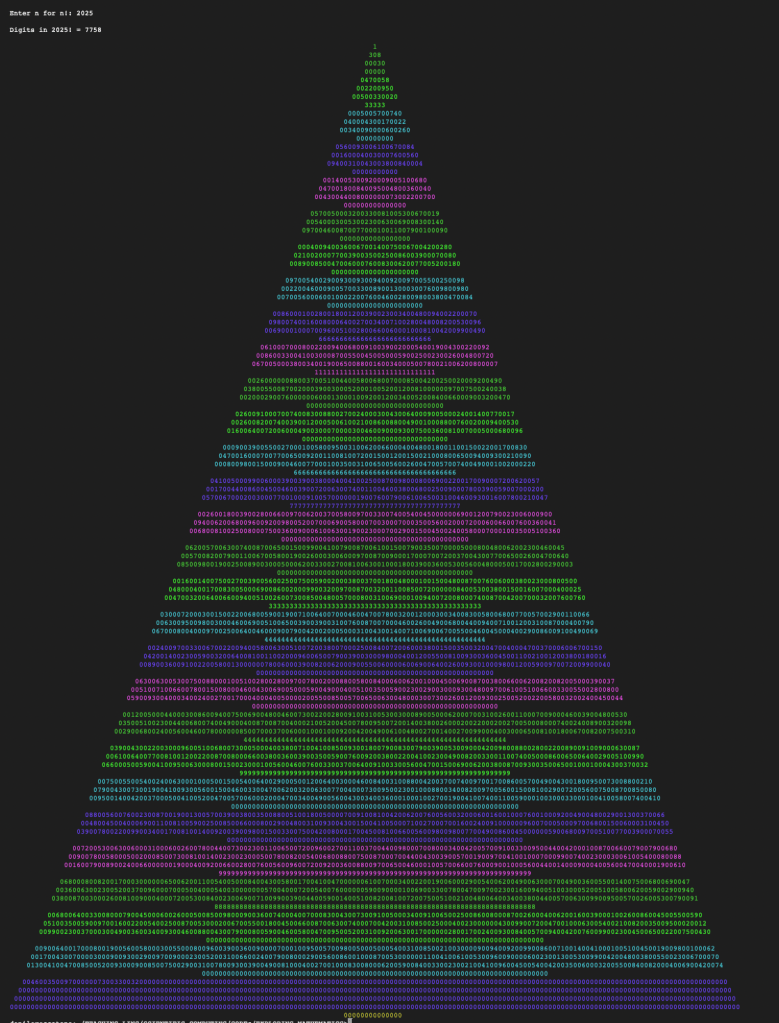

In this post, I will briefly describe the Smith bin algorithm for computing large factorials and present the result for the number 2025, arranged in a geometric form. After all, if numbers are going to grow explosively, why not let them grow into Christmas trees for 2025?

Computing Large Factorials: The Smith Bin Method

The rapid growth of the factorial function presents a very concrete computational problem. Even for modest values of n, the number n! quickly exceeds the size of a single machine word. On early computers—where integers were often limited to 36 or 48 bits—this meant that ordinary arithmetic could no longer be used.

One elegant solution to this problem was described by R. E. Smith in The Bases of FORTRAN (1967). Rather than attempting to store a large number “in one piece,” Smith proposed splitting it into several smaller components, or bins, each capable of holding only a fixed number of decimal digits.

The basic idea

Instead of representing a number as a single integer, it is stored as a sequence of bins:

where:

is a fixed base,

- each bin

satisfies

,

- and each bin holds at most t decimal digits.

In practice, a convenient choice is t = 3 or t = 4, so that each bin fits comfortably within a standard integer type.

Multiplication with carries

To compute a factorial, the bins are updated one multiplier at a time. Starting from 1, the current value is multiplied by 2, then by 3, and so on up to n.

For each multiplication:

- Every bin is multiplied by the current factor.

- Any overflow beyond the allowed t digits is extracted as a carry.

- The carry is added to the next bin to the left.

- This process continues until all bins satisfy the size constraint.

The procedure closely mirrors long multiplication performed by hand, except that each “digit” is itself a small block of digits.

Once the computation is complete, the bins are converted back into a continuous string of decimal digits. Normally, this string would simply be printed as a number. The following pseudocode summarizes Smith’s algorithm

procedure factorial_with_bins(n):

base ← 10^t // each bin holds t digits

bins ← [1] // least significant bin first

for k from 2 to n:

carry ← 0

for i from 0 to length(bins) − 1:

product ← bins[i] × k + carry

bins[i] ← product mod base

carry ← product div base

while carry > 0:

append (carry mod base) to bins

carry ← carry div base

return bins

To illustrate the bin method, let us compute:

We choose a small base

so that each bin holds at most two digits.

The bins are written from least significant to most significant.

We observe that the factorial multiplication until 4 gives a number that fit in one bin as it is less than 99 (no overflow)

bins = [24]

However when we multiply by 5

We now have a bin overflow:

- therefore, we keep

- and carry

bins = [20, 1]

This represents the number:

For the next number (6), we multiply each bin, starting from the least significant.

Bin[0]:

→ keep 20, carry 1

Bin[1]:

Therefore, the final bins are:

bins = [20, 7]

This represents:

Namely the value of the factorial

6! = 720

The computation never required storing a number larger than two digits in any single bin.

Although modern programming languages now provide built-in arbitrary-precision integers, Smith’s method remains conceptually important. It illustrates how large-number arithmetic can be constructed from simple operations, and it anticipates many ideas used in contemporary big-integer libraries. Variants of it appear in:

- arbitrary-precision arithmetic,

- cryptographic software,

- symbolic computation systems,

- and high-precision numerical simulations.

From Numbers to Shapes

Once a large factorial has been computed, it naturally appears as a long string of digits. Normally, we print that string in a single line and move on. But this raises a playful question:

Can the digits of a factorial be arranged so that the number itself takes on a recognizable shape?

Inspired by Gardner’s recreational approach, I decided to explore this question visually. The result is a simple but surprisingly rich idea: use the digits of a factorial to grow a Christmas tree. Small factorials produce simple triangles. Larger factorials naturally generate layered, branching structures—stacked “crowns” that widen as the number of digits increases. Only when enough digits are available does a true tree appear, complete with foliage and a trunk.

Here the Result for 2025