With the help of my lovely assistant, we have just published on Instructables another STEM project. This time, it was inspired by the reading of the classic Comets by Carl Sagan and the upcoming period of significant meteor shower events of the year:

- Perseids: The Perseids is one of the most popular and reliable meteor showers, occurring annually in mid-August. It is associated with the comet Swift-Tuttle and gets its name from the constellation Perseus, from where the meteors appear to radiate. The Perseids are known for their fast and bright meteors, often leaving long-lasting trails in the sky. They are visible from both hemispheres, but the best viewing opportunities are typically in the northern hemisphere. During its peak, the Perseids can produce up to 60 to 100 meteors per hour.

- Geminids: The Geminids meteor shower takes place every December and is considered one of the most reliable and prolific meteor showers of the year. The Geminids are associated with the asteroid 3200 Phaethon and appear to radiate from the constellation Gemini, hence their name. Unlike many other meteor showers, the Geminids can be observed from both the northern and southern hemispheres. They are known for producing bright, colorful meteors and can reach a peak rate of 120 to 160 meteors per hour, making them a spectacular astronomical event.

- Quadrantids: The Quadrantids meteor shower occurs annually in early January and is known for its brief but intense display of meteors. The radiant point of the Quadrantids lies in the defunct constellation Quadrans Muralis, which is no longer recognized as a constellation. However, the meteors can be seen anywhere in the sky. The Quadrantids are associated with the asteroid 2003 EH1, which is believed to be an extinct comet. The peak of the Quadrantids is relatively short, usually lasting only a few hours, but it can produce a high meteor rate of around 60 to 200 meteors per hour.

Who won’t be thrilled by capturing a piece of outer space right in your hands? However, you might think, “But I don’t have the necessary equipment!” Fear not, as luck would have it, you’ve stumbled upon this instructable that will guide you in creating your own Micrometeorite Separator and Spotter (MSS).

Sure, it’s true that if a magnificent carbonaceous chondrite were to gracefully land right in front of your doorstep, you wouldn’t need any equipment. However, chances are high that tiny fragments of meteorites, resembling specks of falling stars, are scattered on your rooftop, waiting to be discovered. Countless websites and YouTube videos share fascinating tales of those who have embarked on this labor of love, showcasing the patience and dedication required to uncover these elusive cosmic treasures. The meteorites you’re after are microscopic, so your search will focus on distinguishing them from the terrestrial dust and debris that pervade our surroundings.

Fortunately, a small and mighty Neodymium magnet proves invaluable in this pursuit, especially for isolating metallic meteorites. Yet, be prepared for a challenging quest, as finding these little celestial gems is no easy task. However, the rewards of discovering even a single meteorite are genuinely remarkable.

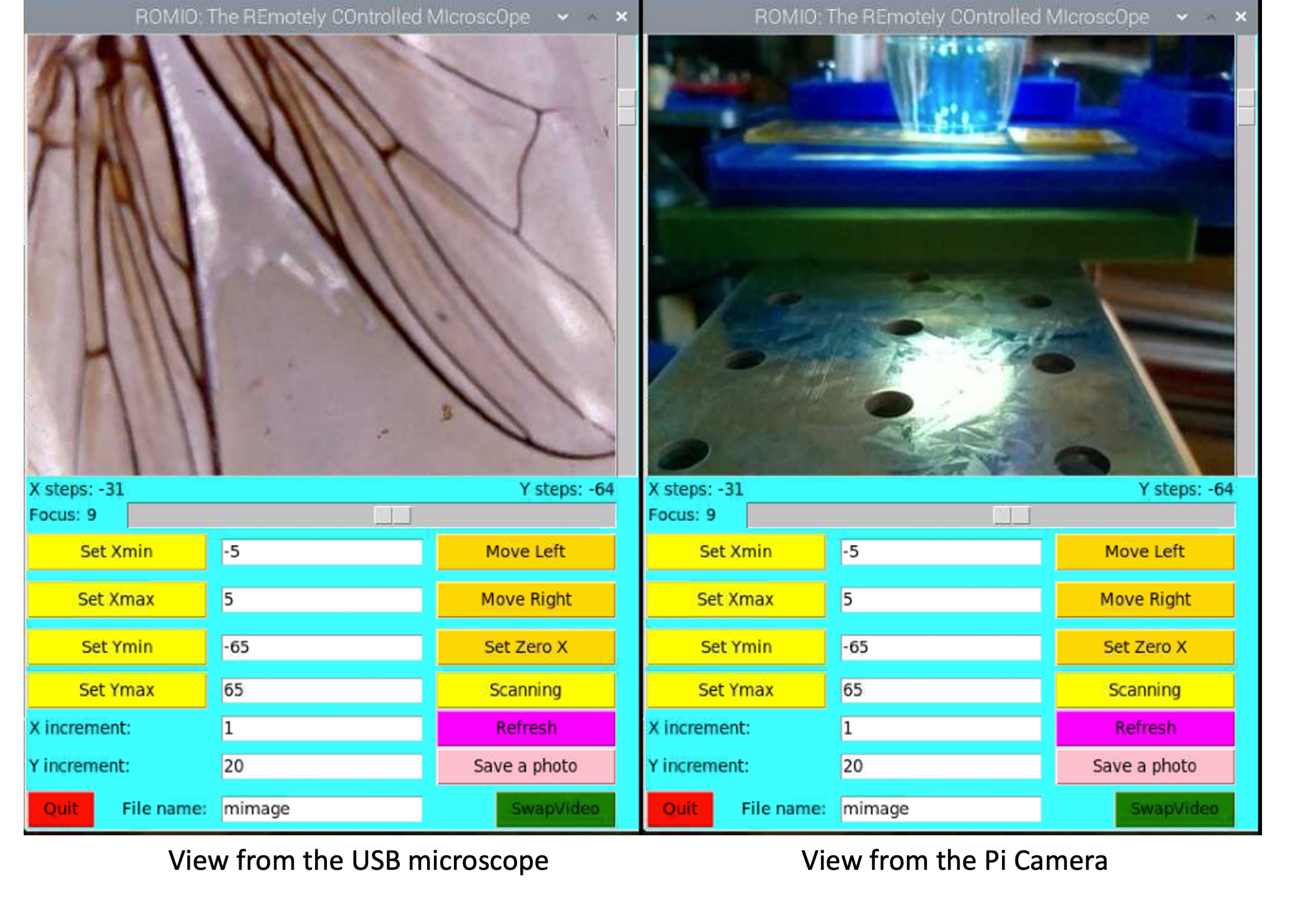

We have recently published an Instructable project presenting a simple yet effective device to aid you in your meteorite discovery journey. This device remains compact and portable that can be used with a digital microscope or fitted under a stereomicroscope and the wonders they reveal.

So, get ready to embark on an extraordinary adventure and immerse yourself in the captivating world of meteorite hunting. With the Micrometeorite Separator and Spotter (MSS) at your disposal, you’ll be equipped to explore the heavens and unveil the hidden secrets within the depths of our vast universe.

Happy hunting, and do not forget to like this post and the Instructable !