Important structural components of proteins, like linker loops and intrinsically disordered regions, are highly flexible and constantly change shape in solution. These flexible protein regions — especially those containing glycine- and serine-rich segments — do not behave like neatly folded proteins. They fluctuate, breathe, and explore broad conformational landscapes. These motions can often be central to biological function. But capturing them consistently, both structurally and dynamically, remains challenging. To understand the physics of this flexibility, we often turn to short model peptides that isolate the essential ingredients of chain dynamics. In an earlier work, we explored glycine- and serine-rich octapeptides using molecular dynamics (MD) simulations in combination with concepts from FRET (Förster Resonance Energy Transfer) spectroscopy. The goal was to understand how flexible chains fluctuate and how these fluctuations are reflected in experimentally measurable distances.

In a new publication in The Journal of Physical Chemistry B [1], we have built directly on that foundation, but push the idea further toward quantitative integration between simulation and experiment. At the center of both studies is a small but powerful fluorescent probe: 2,3-diazabicyclo[2.2.2]oct-2-ene (DBO). Paired with tryptophan, DBO enables measurements of extremely short intramolecular distances. Because it is compact and minimally perturbing, it is particularly well suited for probing flexible peptides that would be difficult to characterize using larger fluorophores. In the earlier work, the focus was primarily on understanding conformational ensembles and distance distributions.

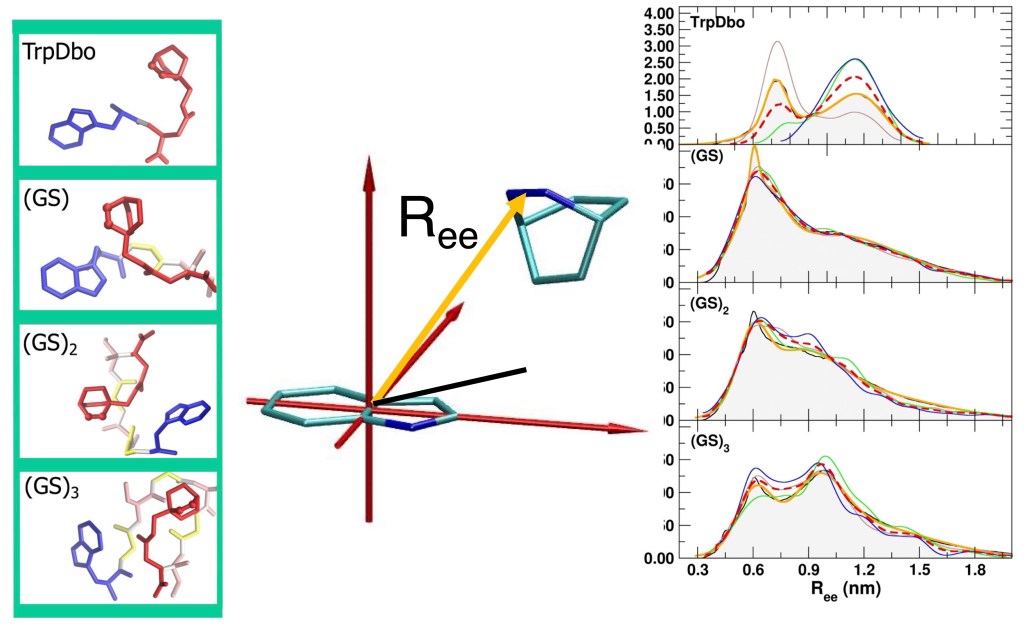

In this new study, the Dbo model has been upgraded to the more recent version of the GROMOS force field (54A7), and using extensive MD simulations, we have verified whether the new model can more quantitatively reproduce both structural and kinetic FRET experimental observables. In particular, we combined time-resolved FRET experiments with microsecond-scale MD simulations to study model peptides of the form Trp–(GS)n–Dbo and Trp–(PP)n–Dbo with n=0,1,2,3, where the glycine–serine sequences represent highly flexible chains, and the polyproline sequences provide a more rigid reference.

The results of the simulations showed:

- Simulated end-to-end distances agree with FRET-derived experimental values within 5% for the flexible (GS)_npeptides.

- Contact formation kinetics (looping rates) quantitatively match experiment once solvent viscosity is properly accounted for.

- The relationship between chain flexibility and fluorophore separation is systematically captured.

Beyond equilibrium averages, we also analyzed time correlations and dynamical fluctuations, linking conformational free-energy landscapes to experimentally observable FRET signals.

Instead, it demonstrates that combining equilibrium FRET distances and time-resolved kinetic data provides a stringent benchmark for simulation models of flexible peptides. Furthermore, this integrated FRET–MD framework with the improved Dbo model can be applied to:

- Flexible linkers in multidomain proteins

- Intrinsically disordered protein segments

- Small proteins undergoing conformational adaptation

REFERENCE

[1] D. Roccatano . Quantitative Integration of FRET and Molecular Dynamics for Modeling Flexible Peptides. J. Phys. Chem. B, (2026-02-27)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcb.5c08148