Surfactants are everywhere in protein science — from biochemical laboratories to industrial detergents. Among them, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) is perhaps the most famous (or infamous), widely used for its ability to bind, deactivate, and often denature proteins. Despite decades of experimental and theoretical work, the molecular details of how surfactants bind to protein surfaces are still not fully understood. In my recent study, “Binding Dynamics of Linear Alkyl-sulfates of Different Chain Lengths on a Protein Surface” [1], I have explored this problem using molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, focusing on how the length of the surfactant’s hydrocarbon chain influences protein binding.

Why Compare SDS and SHS?

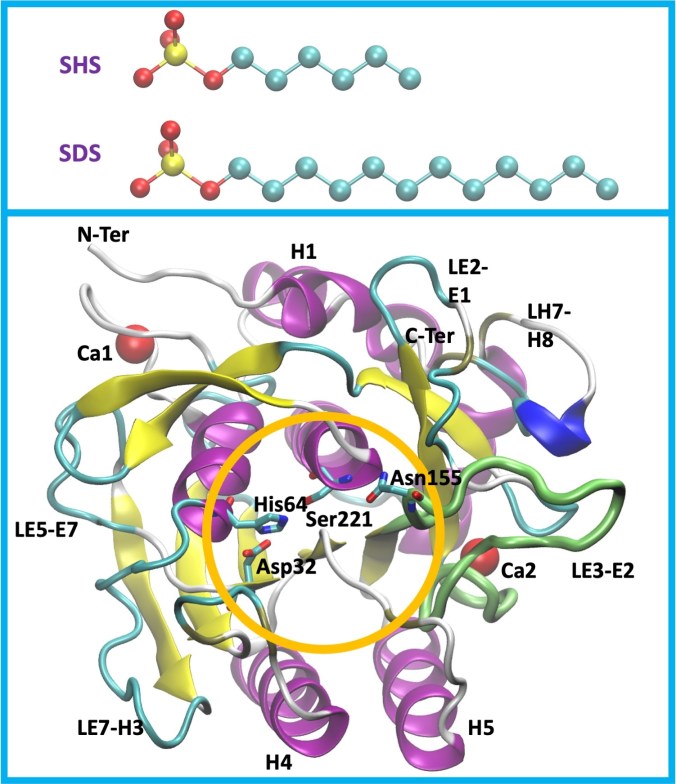

SDS is composed of a negatively charged sulfate headgroup attached to a 12-carbon alkyl chain, while sodium hexyl sulfate (SHS) has a chain that is exactly half as long. This makes SDS and SHS ideal model systems to isolate the role of hydrophobic chain length in surfactant–protein interactions. Both molecules share the same charged headgroup, but differ in how much hydrophobic surface they can present to a protein. This “double anchoring” — electrostatic plus hydrophobic — is a defining feature of alkyl sulfates and sets them apart from classic denaturants like urea or guanidinium chloride.

The Protein: Subtilisin E

The protein of choice is Subtilisin E (SubE), a bacterial serine protease known for its remarkable robustness. SubE remains structurally stable under harsh conditions such as high salt concentrations, organic solvents, and elevated temperatures — properties that make it valuable in industries ranging from detergents and food processing to pharmaceuticals. Interestingly, experiments have shown that SubE can retain much of its secondary structure even in the presence of SDS, while still losing enzymatic activity. This raises a key question: Can surfactants impair protein function without unfolding the protein?

Simulating Early-Stage Binding Events

To address this, we conducted all-atom MD simulations of SubE in water. We used a low concentration of SDS or SHS (0.5% w/v) and observed that experiments suggest functional effects occur before significant denaturation. Our focus shifted from protein unfolding to characterising the dynamics of surfactant binding on the simulation timescale. Specifically, we investigated:

- Where surfactants bind

- How long they stay bound

- Which residues are involved

- How binding depends on chain length

What It was Found

Protein Structure Remains Intact. Neither SDS nor SHS caused significant changes in the overall secondary structure of SubE compared to simulations in pure water. This confirms that functional impairment can occur without structural collapse.

SDS Binds More Strongly Than SHS. Residue-level contact analysis revealed that SDS interacts more extensively with the protein surface than SHS, especially in α-helices and turn regions. The longer alkyl chain of SDS provides stronger hydrophobic interactions, increasing both contact frequency and binding persistence.

Binding Near the Active Site. One of the most striking results is that SDS preferentially binds near key functional residues, including: Asp32, His64, and Ser221 (the catalytic triad), and Asn155, part of the oxyanion hole These interactions were largely absent for SHS. This offers a compelling molecular explanation for the experimentally observed reduction in enzymatic activity: the protein remains folded, but the active site becomes partially blocked or dynamically perturbed.

Distinct Binding Dynamics. Surfactant molecules rapidly associate with the protein surface — typically within the first 10–25 ns of simulation time. SDS shows more dynamic, transient binding, frequently relocating across the surface. SHS, once bound, tends to remain attached longer but explores fewer binding sites. This highlights how chain length modulates not just binding strength, but binding behavior.

Why This Matters

Understanding how surfactants interact with proteins at the molecular level has practical implications far beyond fundamental biophysics:

- Detergent formulation: designing enzymes that remain active in surfactant-rich environments

- Protein engineering: modifying surface residues to resist functional inhibition

- Biotechnology and pharmaceuticals: preserving enzyme activity under processing conditions

Our results show that small molecular changes — such as halving a hydrocarbon chain — can lead to qualitatively different protein interaction profiles. This study provides a detailed molecular map of how linear alkyl sulfates bind to a protein surface and demonstrates that protein inactivation does not necessarily require denaturation. Instead, subtle and persistent interactions near functional regions may be sufficient. By combining molecular dynamics simulations with experimental insights, we can move toward rational strategies for engineering surfactant-resistant proteins, a goal that is increasingly relevant in industrial and biomedical applications.

REFERENCE

[1] D.Roccatano.Binding dynamics of linear alkyl-sulfates of different chain lengths on a protein surface. Journal of Molecular Liquids, 414, 126168 (2024). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2024.126168