It has become a recurrent habit for me to write a blog on the shape of eggs to wish you a Happy Easter. Not repeating oneself and finding a new interesting topic is a brainstorming exercise of lateral thinking and a systematic search in literature to find an interesting connection. This year, I wanted to explore an idea that has been lurching in my mind for some time for other reasons: billiards.

I used to play snooker from time to time with some old friends. I am a far cry from being even an amateur in the billiard games, but I had a lot of fun verifying the laws of mechanics on a green table. I soon discovered that studying the dynamics of bouncing collision of an ideal cue ball in billiards of different shapes keeps brilliant mathematicians and physicists engaged in recreational academic studies and important theoretical implications.

However, the billiard studied but in mathematical physics, a mathematical billiard, namely a dynamical system in which a point particle moves in a straight line within a domain (the billiard table and reflects elastically off the boundary. The reflection rule follows the law of specular reflection: the angle of incidence equals the angle of reflection. The particle experiences no forces except during collisions with the boundary.

A quadrilateral billiard has been well studied and understood for an obvious reason, but it is still not possible to other polygonal shape table as simple as the triangular one to answer basic questions about the possible trajectories of billiard. Can a ball perform a periodic orbit when it is hit under certain conditions? When the polygonal shape become more complex, it’s not possible to predict the trajectory from one point to another of the table. For convex not polygonal billiard the behavior can be more complex as they generate non-periodic chaotic trajectories.

The mathematical billiard have been classified as follows

- Polygonal Billiards: Linear motion inside polygons; dynamics range from regular to complex, especially in rational polygons.

- Elliptic and Circular Billiards: Integrable systems with smooth boundaries; known for invariant curves (caustics).

- Dispersing Billiards (Sinai): Domains with convex scatterers; exhibit strong chaos and ergodicity.

- Focusing Billiards: Inward-curved boundaries (e.g., stadium); show chaotic behavior due to focusing effects.

- Mixed-Type Billiards: Combine dispersing and focusing parts; produce both chaotic and regular dynamics.

- Generalized Billiards: Include magnetic or outer billiards; dynamics may occur in non-Euclidean settings.

A very good introduction to the mathematical billiard is given by Tabachnikov (see bibliography). Investigated billiard shapes closest to those of bird eggs are the elliptical and its deviations as oval shapes. To the best of my knowledge, I could not find any studies in the literature on egg-shaped billiards that deviate significantly from these analysed shapes.

EGG-SHAPED BILLIARD

For an egg-shaped billiard, we can use a smooth, convex asymmetric boundary inspired by the Hügelschäffer model, for example:

Here, the parameter controls the asymmetry or “eggness” of the shape, while

is a baseline vertical scaling constant (typically

in biological models). The shape becomes more elliptical as

. The parameters

define the approximate semiaxes of the egg envelope. Variants of this three-parameter equation have been proposed to model real bird egg profiles in the literature (see references).

Egg-shaped billiards are considered smooth, convex, and non-integrable for . They are also mixed-type systems due to the coexistence of regular and chaotic regions in phase space. The study of the properties of such types of systems is fascinating, and there is a huge amount of literature due to implications in dynamical systems, ergodic theory, and chaos theory.

I started to explore the topics but writing a Python program capable of making simulations in which it is possible to change the position of the cue and the direction of its initial trajectory and analyze the trajectory. However, I soon realized that it would be more interesting to study the residence time of a cue ball in such a billiard when a leak is present in aone or more region of the billiard border. This process can be analyzed by calculating the first passage time, namely the average time required for the cue to exit the egg. It is also related to the physical phenomenon of Knudsen effusion, namely the diffusion of gas from confined regions through openings in the confinement walls. An excellent review on leaking chaotic systems can be found in the bibliography.

So I started to scratch the surface of this well-investigated area of mathematical physics and probably I will come back to this topic in the future. However, for my recurrent Easter article on eggs, I thought that it would be interesting to create a physical device of such a billiard that can be used to produce an analogue simulation of this process using my other dear hobby: 3D printing. Therefore, in this first article on the mathematical billiards, as a celebration of Easter 2025, I will present this device, and I hope you can enjoy its usage.

The 3d printed Egg-shaped billiard

I have used, as in my previous projects, the parametric Openscad software to produce a 2D profile of the egg. I have used a simplified polar approaximation to the Hugelschaeffer’ egg shape to describe the function.

function hugelschaeffer_egg(t,a,b) = [

//Simplified Polar Approximation

a*cos(t * 180 / PI),

b*(b1 + epsilon * cos(t * 180 / PI)) * sin(t * 180 / PI)

];

The curve is then generated using the command

function generate_egg_curve(a_, b_) = [

for (i = [0 : points - 1])

hugelschaeffer_egg(i * 2 * PI / points, a_, b_)

];

Understanding the Parameters of Our Egg-Shaped Design

This model is inspired by the Hügelschäffer egg curve and enhanced with features such as layered shells and perimeter leaks. Here’s what each parameter controls in the design:

// ===================================

// Parameters

// ===================================

a = 30; // Major axis

b = 30.0; // Minor axis

b1 = 0.8; // Baseline shape constant

epsilon = 0.1; // Egginess factor (Hügelschäffer 'k')

points = 300; // Curve resolution

lh = 90; // Leak spacing

lw = 2.1; // Leak width

Size Parameters. The values a and b define the overall dimensions of the egg. The parameter a controls the width (major axis), and b controls the height (minor axis). When they are equal, the egg has a balanced silhouette, but still retains its asymmetric character due to the shape modifiers.

Shape Modifiers. The parameter b1 sets the baseline of the vertical profile—it shapes the curvature of the lower half of the egg. A smaller b1 flattens the base, while a larger one rounds it. The parameter epsilon adjusts the “egginess” of the shape, determining how sharply the top tapers and how elongated the body becomes. This parameter corresponds to the “k” value in Hügelschäffer’s original egg-shape model.

Curve Resolution. The points parameter controls how many points are used to generate the curve. A higher value means a smoother and more detailed contour, which is especially important when the egg is used for 3D printing or decorative modeling.

Leak Configuration. The parameter lh sets the angular spacing between leak holes arranged around the egg—essentially how many degrees apart each one is. The variable lw sets their width.

These parameters give you fine control over both the geometric shape and the additional structures built into the design. Together, they allow for a highly customizable and expressive egg-shaped object, suitable for decorative use, modeling, or interactive features.

In the appendix, the complete code is provided.

RESULTS

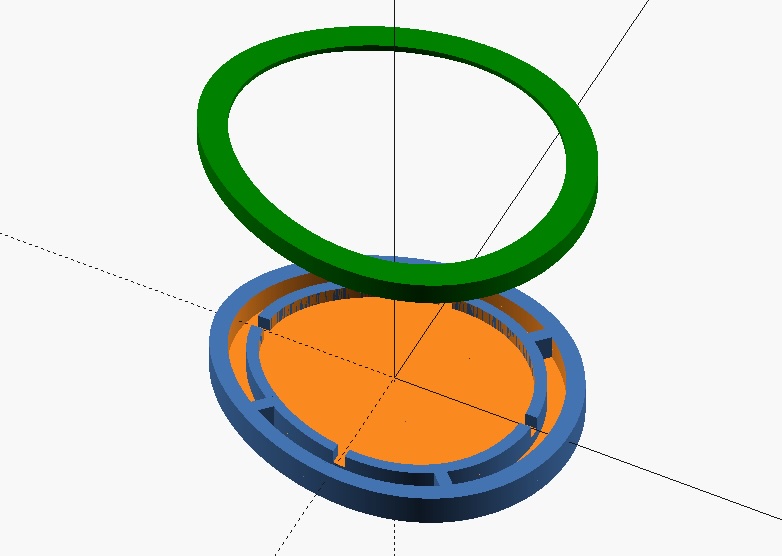

Here is the picture of the OpenSCAD model of the base and lead obtained using the parameters in the script.

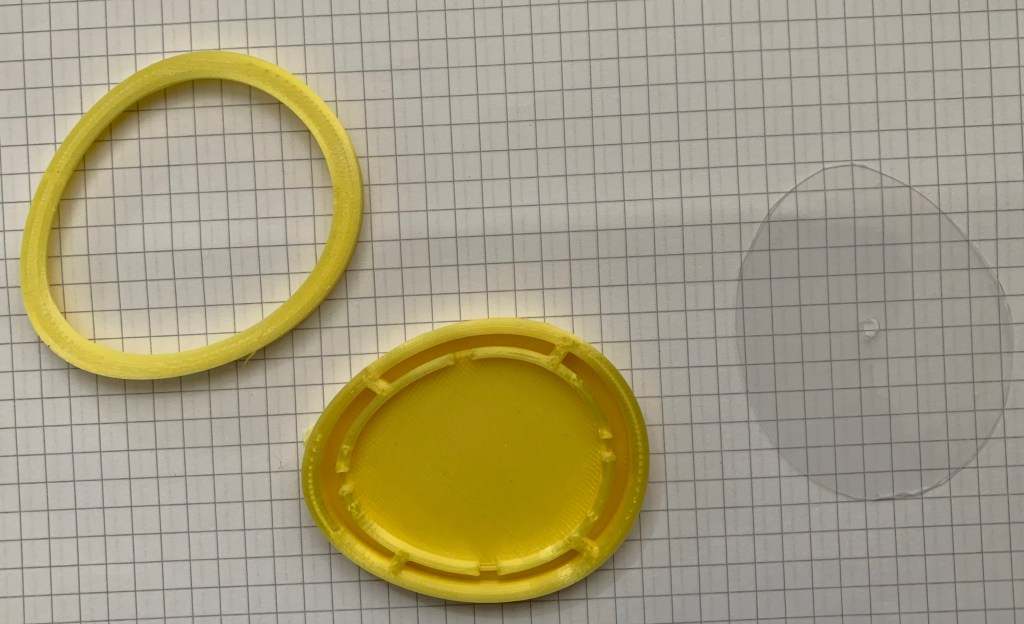

The 3D-printed billiard using 1.4 mm PLA filament with a Creality 5 Pro is shown in the next figure.

Using a polyacetate transparent plastic sheet, cut a shape (right) that fits inside the lid part (left). Punch a hole in its center that will be used to fill the steel cue balls. The final assembly, loaded with the 14 steel balls, is shown in the next figure.

Design and Function of the 3D-Printed Egg-Shaped Billiard

The 3D-printed billiard device is composed of two main components: a base and a lid.

The lid is shaped to match the egg contour and is topped with a thin acetate sheet, also cut into an egg profile. At the center of this sheet, a small hole allows the user to insert steel bearing balls, which act as cues.

The base complements the lid and encloses the inner arena where the balls are free to move. Once the balls are loaded, the lid is placed securely onto the base.

How It Works

To initiate motion, the user gives the device a light shake while keeping it level on a flat surface. This impulse sets the steel balls into motion, allowing them to bounce around inside the egg-shaped boundary. The walls of the internal arena feature narrow slots designed to interact with the motion of the balls. When a ball successfully enters one of these slots, it passes through and falls into a small ditch positioned behind the opening. This clever feature prevents the ball from returning to the arena, ensuring that each successful “hit” is effectively counted or removed from play.

This setup creates a miniature, probabilistic billiard game, where random motion, shape design, and slot placement combine into a dynamic interaction. It’s both a playful demonstration and an engaging visualization of kinetic behavior within a bounded asymmetric geometry.

I hope you have fun with this device, and if you have tried it and have suggestions, do not hesitate to write a comment . Please also subscribe to the website if you want to stay informed of new articles.

HAPPY EASTER 2025!

ESSENTIAL BIBLIOGRAPHY

Mathematical billiards and leaking chaotic systems.

- Tabachnikov, S., 2005. Geometry and billiards (Vol. 30). American Mathematical Soc.. (An excellent introduction with a well-balanced of mix of theory, classification, and beautiful geometric intuition.)

- Altmann, E. G., Portela, J. S. E., and Tél, T. (2013)Leaking chaotic systems. Rev. Mod. Phys., 85, 869. (Excellent review of open chaotic systems, escape rates, and their mathematical structure.)

Mathematical modelling of bird’s eggs

- Narushin, V.G., Volkova, N.A., Dzhagaev, A.Y., Griffin, D.K., Romanov, M.N. and Zinovieva, N.A., 2025. Coupling artificial intelligence with proper mathematical algorithms to gain deeper insights into the biology of birds’ eggs. Animals, 15(3), p.292.An interesting, very recent review on bird egg modelling equations.

APPENDIX

Here the complete openSCAD script. To use you need to copy and past in openSCAD program. To generate the base uncomment the baseNew(); module to generated the lead use the TopNew(); module.

$fn = 100;

// ===================================

// Parameters

// ===================================

a = 30; // Major axis

b = 30.0; // Minor axis

b1 = 0.8; // Baseline shape constant

epsilon = 0.1; // Egginess factor (Hügelschäffer 'k')

points = 300; // Curve resolution

lh = 90; // Leak spacing

lw = 2.1; // Leak width

hlh = lh / 2;

steps = floor(360 / lh); // Number of leak rotations

// ===================================

// Egg Curve Generators

// ===================================

function hugelschaeffer_egg(t, a, b) = [

a * cos(t * 180 / PI),

b * (b1 + epsilon * cos(t * 180 / PI)) * sin(t * 180 / PI)

];

function generate_egg_curve(a_, b_) = [

for (i = [0 : points - 1])

hugelschaeffer_egg(i * 2 * PI / points, a_, b_)

];

index_path = [ for (i = [0 : points - 1]) i ];

// ===================================

// Curves for different shell layers

// ===================================

egg_curve = generate_egg_curve(a, b);

egg_curve1 = generate_egg_curve(a - 3.0, b - 3.0);

egg_curve2 = generate_egg_curve(a - 6.0, b - 6.0);

egg_curve3 = generate_egg_curve(a - 8.0, b - 8.0);

egg_curve4 = generate_egg_curve(a + 2.0, b + 2.0);

egg_curve5 = generate_egg_curve(a + 0.2, b + 0.2);

// ===================================

// Modules

// ===================================

module Border() {

difference() {

translate([0, 0, 0.0])

linear_extrude(height = 3.0)

polygon(points = egg_curve1, paths = [index_path]);

translate([0, 0, -4.0])

linear_extrude(height = 8.0)

polygon(points = egg_curve2, paths = [index_path]);

// Radial leaking slits

for (i = [0 : steps - 1])

rotate([0, 0, i * lh + hlh])

cube([100, 2.0, 10], center = true);

}

}

module Border1() {

difference() {

translate([0, 0, 0.0])

linear_extrude(height = 3.0)

polygon(points = egg_curve2, paths = [index_path]);

translate([0, 0, -4.0])

linear_extrude(height = 8.0)

polygon(points = egg_curve3, paths = [index_path]);

for (i = [0 : steps - 1])

rotate([0, 0, i * lh])

cube([100, lw, 10], center = true);

}

}

module TopNew() {

difference() {

translate([0, 0, -2])

linear_extrude(height = 4)

polygon(points = egg_curve4, paths = [index_path]);

translate([0, 0, -2.0])

linear_extrude(height = 6.0)

polygon(points = egg_curve1, paths = [index_path]);

translate([0, 0, -3.0])

linear_extrude(height = 4.0)

polygon(points = egg_curve5, paths = [index_path]);

}

}

module BaseNew() {

difference() {

translate([0, 0, -4.0])

linear_extrude(height = 5.5)

polygon(points = egg_curve, paths = [index_path]);

translate([0, 0, -3.0])

Border();

translate([0, 0, -1.0])

linear_extrude(height = 6.0)

polygon(points = egg_curve1, paths = [index_path]);

}

// Secondary border decoration

translate([0, 0, -1.5])

Border1();

// Inner slits intersection

difference() {

intersection() {

for (i = [0 : steps - 1])

rotate([0, 0, i * lh + hlh])

cube([100, 2.0, 3], center = true);

translate([0, 0, -1.5])

linear_extrude(height = 3.0)

polygon(points = egg_curve, paths = [index_path]);

}

translate([0, 0, -1.0])

linear_extrude(height = 6.0)

polygon(points = egg_curve3, paths = [index_path]);

translate([0, 0, -1.5])

Border1();

}

}

// Uncomment to render

//BaseNew();

// TopNew();